Fentanyl Linked to 94% of Overdose Deaths in Massachusetts

/By Pat Anson, PNN Editor

There’s good and bad news in the latest report on overdose deaths in Massachusetts. State health officials say drug deaths were down slightly in the first nine months of 2022, compared to the same period last year. But deaths involving fentanyl – most likely illicit fentanyl -- rose to 94% of opioid-related overdoses, a record high.

Massachusetts was one of the first states in the U.S. to expand the use of toxicology tests to look for the presence of certain drugs involved in opioid overdoses, instead of just relying on death certificates and coroner reports. That makes its overdose data more accurate.

In the first nine months of 2022, there were 1,340 confirmed opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts, and officials expect that to reach about 1,696 deaths by the end of the year. That’s 25 fewer deaths than in 2021, a decrease of 1.5 percent.

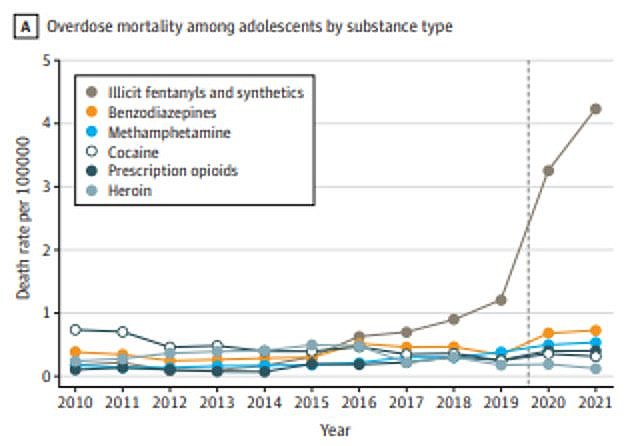

Nationally, drug overdose deaths also appear to be slowing. The CDC estimates there were 107,735 U.S. overdose deaths in the 12-month period ending in July 2022, down from over 110,000 deaths in the 12-month period that ended in March, 2022. Illicit fentanyl, a synthetic opioid about 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, is involved in the vast majority of those deaths.

Deaths in Massachusetts involving a fentanyl have been rising for over a decade, from nearly 42% of opioid-related overdoses in 2014 to 94% this year. Over that same period, deaths involving prescription opioids such as oxycodone and hydrocodone have steadily declined from about 35% to 11% of overdoses in 2022.

More people are now dying in Massachusetts after ingesting fentanyl, cocaine, alcohol or benzodiazepines such as Xanax than from pain medication. Deaths linked to opioid medication fell by 30% in just one year, which coincides with a steep decline in prescriptions in Massachusetts over the past decade.

Drugs Involved in Massachusetts Opioid-Related Overdose Deaths

Massachusetts Department of Public Health

“Every life lost to opioid overdose is its own tragedy,” Public Health Commissioner Margret Cooke said in a statement. “With this report, we are encouraged by the decrease, however modest, in opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts so far this year. We will continue to build on our data-driven and equity-based public health approach as we address the impacts of the opioid epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic, especially among vulnerable populations.”

Health officials say the illicit drug supply in Massachusetts is “heavily contaminated” with illicit fentanyl, which is frequently used in the manufacture of counterfeit medication sold on the street.

Pharmaceutical fentanyl is used as a surgical analgesic and in patches and lozenges to treat severe pain, but only small amounts are diverted for abuse. The DEA estimates that only 0.01% of prescription fentanyl is diverted for use by someone it was not intended for.

It's important to note that the presence of a drug found in a toxicology screen doesn’t mean it was the cause of someone’s death. Multiples substances are frequently involved in opioid overdoses, and the official cause of death is a clinical decision made by coroners and medical examiners.

Toxicology tests alone also don’t reveal if a prescribed drug was intended for the decedent, or if it was bought, stolen or borrowed by them. An earlier study of drug deaths in Massachusetts found that only 1.3% of overdose victims had a prescription for the opioid medication involved in their deaths.

The vast majority of patients prescribed opioids use them responsibly and don’t go doctor shopping. The Massachusetts Department of Public Health estimates that only 0.6% of patients who were prescribed an opioid this year had an “activity of concern,” such as getting prescriptions from multiple providers or having them filled at multiple pharmacies.