Placebo Effect is All in Our Heads

/By Pat Anson, Editor

A new study has given researchers a better understanding why some people given a simple sugar pill will say it significantly reduces their pain.

It’s all in their heads.

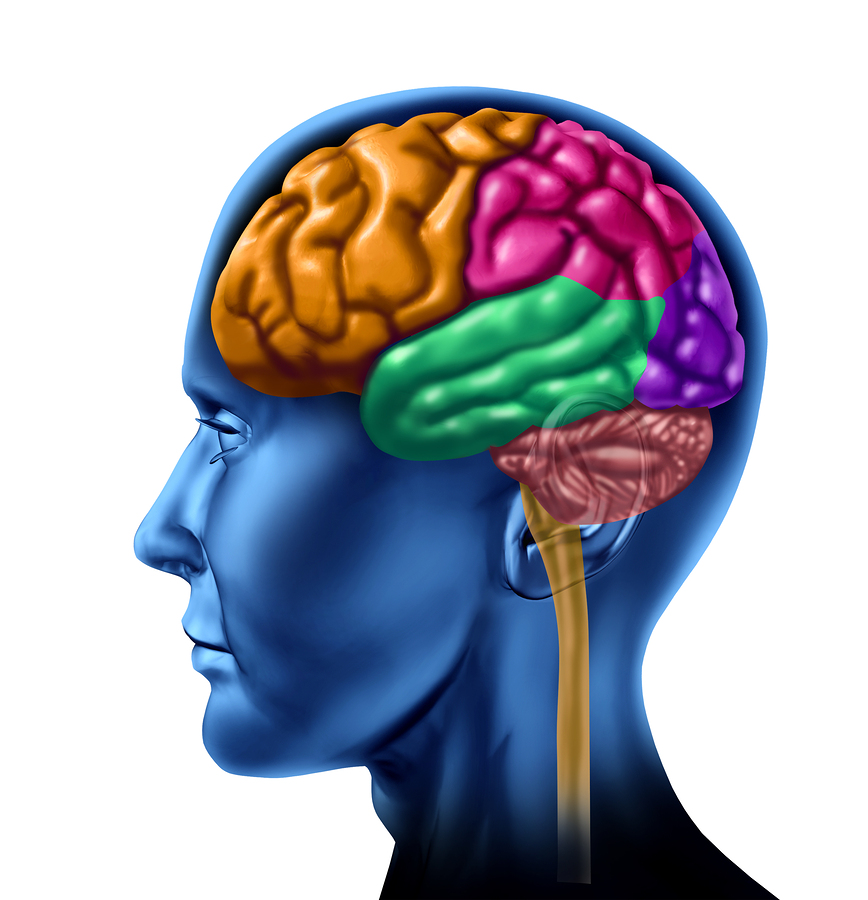

Using functional magnetic resonance brain imaging (fMRI), scientists at the Northwestern Medicine and the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (RIC) have identified for the first time the region of the brain that's responsible for the "placebo effect" in pain relief. It’s an area in the front part of the brain -- called the mid frontal gyrus -- that also plays a key role in our emotions and decision making.

In two clinical trials involving 95 patients with chronic pain from osteoarthritis, researchers found that about half of the participants had mid frontal gyrus that had more connectivity with other parts of the brain and were more likely to respond to the placebo effect.

The use of fMRI images to identify these “placebo responders” and eliminate them from clinical trials could make future research far more reliable. It could also lead to more targeted pain therapy based on a patient’s brain images, instead of a trial-and-error approach that exposes patients to ineffective and sometimes dangerous medications.

"Given the enormous societal toll of chronic pain, being able to predict placebo responders in a chronic pain population could both help the design of personalized medicine and enhance the success of clinical trials," said Marwan Baliki, PhD, a research scientist at RIC and an assistant professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

“This can help us better conduct clinical studies by screening out patients that respond to placebo and we can just include patients that do not respond. And we can measure the efficacy of a certain drug in a much more effective manner.”

Baliki told Pain News Network that differences in the brain could explain why some prescription drugs – such as Lyrica (pregabalin) – are effective in giving pain relief to some patients, but not for others.

“If we do the same with Lyrica, maybe we can find another area of the brain that can predict the response to that drug,” he said.

The study findings are being published in PLOS Biology.

"The new technology will allow physicians to see what part of the brain is activated during an individual's pain and choose the specific drug to target this spot," said Vania Apkarian, a professor of physiology at Feinberg and study co-author. "It also will provide more evidence-based measurements. Physicians will be able to measure how the patient's pain region is affected by the drug."

Currently, most clinical studies involving pain are conducted on healthy subjects in controlled experimental settings. Those experiments usually induce acute pain through immersion in cold water, pressure or some other type of applied pain. Baliki says there are significant differences between acute and chronic pain, and the experiments often translate poorly in clinical settings where pain is usually chronic.