$23 Billion Raised for Rare Disease Drug Development

/By Roger Chriss, PNN Columnist

Monday, February 28 is Rare Disease Day, a global effort to recognize and raise awareness of rare diseases. The annual event has been held every year since 2008, but has taken on a new tenor amid Covid-19. Long Covid has become one of the biggest threats the coronavirus poses. But like rare diseases, long Covid is not often discussed in public health messaging about the pandemic.

The National Organization of Rare Disorders officially recognizes over 7,000 rare diseases. But the actual number is much higher. Each year some 250 new rare diseases are identified, and existing rare diseases like Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and Ehlers-Danlos syndromes have new types and subtypes identified.

Rare diseases are often only familiar to the people who live with them and the specialists who treat them. For the goal of treatment to be met, rare diseases must be named and characterized. In Europe, a disease is classified as rare if it affects fewer than 1 in 2,000 people, while in the U.S. rare diseases are recognized as conditions that affect fewer than 200,000 people nationally.

They may be rare, but their impact is substantial. A recent study in the Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases estimates that rare diseases affect 25 to 30 million people in the U.S. and more than 300 million people worldwide. Patients and their families have to endure a lengthy “diagnostic odyssey,” often at high financial and emotional cost.

The graphic below helps demonstrate the many barriers that a rare disease patient may encounter in getting a proper diagnosis, such as lack of knowledge about a disease, an overlap of symptoms, lack of diagnostic tests, and inaccurate test results.

According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, the total cost of rare diseases in 2019 reached $966 billion, counting both direct medical costs and other indirect expenses such as loss of income. But research funding for rare disease has long been limited, in part because of the difficulty in diagnosing them.

Fortunately, that may be changing. A new report by the non-profit Global Genes estimates that nearly $23 billion was raised in 2021 from public and private sources to fund rare disease drug development. That’s a 28 percent increase over the money raised in 2020.

“Rare diseases continue to have a strong allure to investors, as evidenced by the significant capital raised in 2021 to advance companies and pipelines focused on rare conditions,” said Craig Martin, CEO of Global Genes. “We hope and expect that the sector will continue to be strengthened by the vast array of opportunities to advance promising biotechnologies, under expedited review, that can address the tremendous burdens and underlying causes of thousands of rare, genetic conditions currently without approved treatments.”

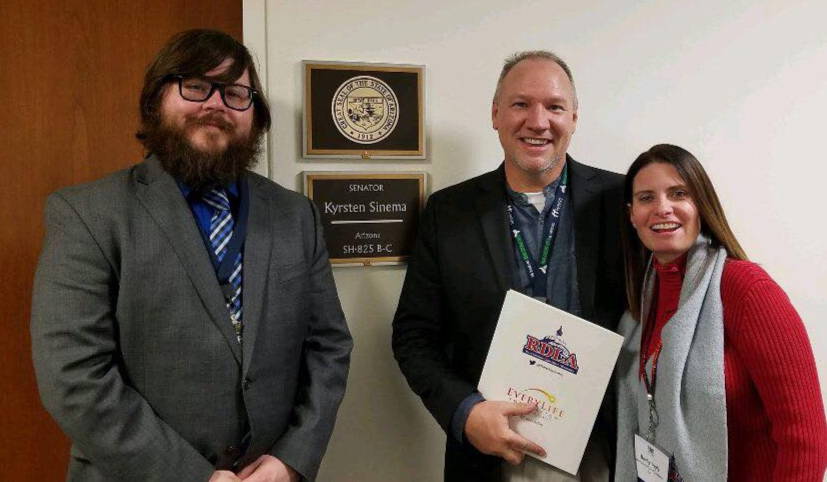

The past year saw many positive steps toward improving the diagnosis and treatment of rare diseases. Congress is considering the Speeding Therapy Access Today (STAT) Act of 2021, which requires policy reforms at the FDA to speed up the development of treatments for rare diseases.

Although the STAT Act has yet to pass, the FDA has already taken action to address two rare diseases. The agency recently approved Pyrukynd (mitapivat) tablets to treat hemolytic anemia in adults with pyruvate kinase deficiency and Vyvgart (efgartigimod) for the treatment of generalized myasthenia gravis.

The past year also saw efforts to improve research and data collection for rare diseases. AllStripes added 100 rare disease research programs to its efforts, and RARE-X launched its initial set of data collection programs. And Rare Diseases International started its Collaborative Global Network for Rare Diseases to create a “a person-centered network of care and expertise” for people living with rare diseases.

But more work needs to be done. The EveryLife Foundation for Rare Diseases notes that 93% of rare diseases have no FDA-approved treatment. In some cases, the pathophysiology is not well understood and animal models do not even exist. In other cases, although the disease is known and treatments do exist, there are too few clinicians and too little financial support for patients.

For people with rare diseases, every day is “rare disease day.” Hopefully efforts to recognize and increase awareness of rare diseases will promote more progress in their diagnosis and treatment.

Roger Chriss lives with Ehlers Danlos syndrome and is a proud member of the Ehlers-Danlos Society. Roger is a technical consultant in Washington state, where he specializes in mathematics and research.