FDA to Review All Abuse Deterrent Opioids

/By Pat Anson, Editor

A week after asking that Opana ER be taken off the market, the head of the Food and Drug Administration has ordered a review of all opioid painkillers with abuse deterrent formulas to see if they actually help prevent opioid abuse and addiction.

The move is likely to add to speculation that the FDA may seek to prevent the sale of other opioid painkillers.

“We are announcing a public meeting that seeks a discussion on a central question related to opioid medications with abuse-deterrent properties: do we have the right information to determine whether these products are having their intended impact on limiting abuse and helping to curb the epidemic?” FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said in a statement.

Gottlieb said the FDA would meet with “external thought leaders” on July 10th and 11th to assess abuse deterrent formulas, which usually make medications harder for addicts to crush or liquefy for snorting and injecting. He did not identify who the thought leaders were.

“Opioid formulations with properties designed to deter abuse are not abuse-proof or addiction-proof. These drugs can still be abused, particularly orally, and their use can still lead to new addiction,” Gottlieb said. “Nonetheless, these new formulations may hold promise as one part of a broad effort to reduce the rates of misuse and abuse. One thing is clear: we need better scientific information to understand how to optimize our assessment of abuse deterrent formulations.”

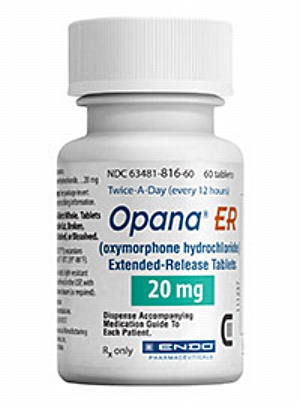

In a surprise move last week, the FDA asked Endo Pharmaceuticals to remove Opana ER from the market, citing concerns that the oxymorphone tablets are being liquefied and injected. It’s the first time the agency has taken steps to stop an opioid painkiller from being sold.

“I am pleased, but not because I think that this one move by itself will have much impact,” Andrew Kolodny, MD, Executive Director of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing (PROP) told Mother Jones. “I’m hopeful that this signals a change at FDA—and that Opana might be just the first opioid that they’ll consider taking off the market. It’s too soon to tell.”

Opana was reformulated by Endo in 2012 to make it harder to abuse, but addicts quickly discovered they could still inject it. The FDA said Opana was linked to serious outbreaks of HIV, Hepatitis C and a blood clotting disorder spread by infected needles.

Endo has yet to respond to the FDA request. If the company refuses to stop selling Opana, the agency said it would take steps to require its removal from the market by withdrawing approval.

“The request to voluntarily remove the product is one thing, but it comes with a lot of other questions that are unanswered,” Endo CEO Paul Campanelli reportedly said at an industry conference covered by Bloomberg. “We are attempting to communicate with the FDA to find out what they would like us to do.”

Patient advocates say it would be unfair to remove an effective pain medication from the market just because it is being abused by addicts.

“The FDA is following a political agenda, rather than its mandate to protect the public health,” said Janice Reynolds, a retired oncology nurse who suffers from persistent pain. “Depriving those who benefit from the use of Opana ER to stop people from using it illegally is ethically and morally wrong.”

Sales of Opana reached nearly $160 million last year. The painkiller is prescribed about 50,000 times a month.

"This is something that could potentially apply to other drugs in the future, as it may signal a movement by the FDA to start taking products off the market that don't have strong abuse-deterrent properties," industry analyst Scott Lassman told CorporateCounsel.com.

The FDA put drug makers on notice four years ago that they should speed up the development of abuse deterrent formulas (ADF). Acting on the FDA's guidance, pharmaceutical companies spent hundreds of millions of dollars developing several new opioid painkillers that are harder to chew, crush, snort or inject.

Were they worth the investment? Not according to a recent study funded by insurers, pharmacy benefit managers and some drug makers.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER), a non-profit that recommends which medications should be covered by insurance and at what price, released a report last month that gave ADF opioids a lukewarm grade when it comes to preventing abuse.

“Without stronger real-world evidence that ADFs reduce the risk of abuse and addiction among newly prescribed patients, our judgment is that the evidence can only demonstrate a ‘comparable or better’ net health benefit (C+),” the ICER report states.

The insurance industry has been reluctant to pay for ADF opioids, not because of any lack of effectiveness in preventing abuse, but because of their cost. A branded ADF opioid like OxyContin can cost nearly twice as much as a generic opioid without an abuse deterrent formula. According to one study, OxyContin was covered by only a third of Medicare Part D plans in 2015. Many insurers also require prior authorization before an OxyContin prescription is filled.