FTC Sues Drug Makers for Oxymorphone Monopoly

/By Pat Anson, PNN Editor

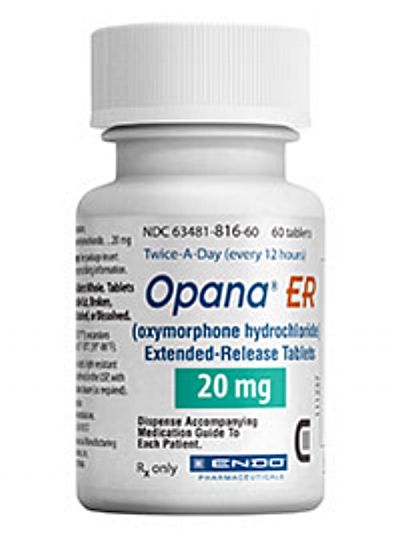

It was in 2017 that Endo Pharmaceuticals – under pressure from the Food and Drug Administration -- stopped selling Opana ER, an extended-release version of the opioid painkiller oxymorphone. Opana had been reformulated by Endo to make it harder to abuse, but the FDA maintained the tablets were still being crushed, liquefied and then injected by illicit drug users.

Although Opana has been off the market for nearly four years, a legal battle still rages over sales of generic oxymorphone and whether Endo conspired with another drug maker to control the market for oxymorphone.

This week the Federal Trade Commission sued Endo, Impax Laboratories, and Impax’s owner, Amneal Pharmaceuticals, alleging that a 2017 agreement between Endo and Impax violated antitrust laws by eliminating competition for oxymorphone ER.

It’s the second time the FTC filed complaints against Endo, Impax and Amneal for allegedly creating an oxymorphone monopoly.

“The agreement between Endo and Impax has eliminated the incentive for competition, which drives affordable prices,” Gail Levine, Deputy Director of the FTC’s Bureau of Competition said in a statement. “By keeping competitors off the market, the agreement lets Impax continue to charge monopoly prices while Endo and Impax split the monopoly profits.”

According to the FTC complaint, Opana ER generated nearly $160 million in revenue for Endo in 2016 and was the company’s “highest-grossing branded pain management drug.” Endo explored bringing another oxymorphone drug on the market to replace its lost revenue, but ultimately decided to partner with Impax, which had the only extended-release oxymorphone drug on the market.. Their agreement allowed Endo to share in Impax’s oxymorphone profits, as long as Endo did not bring another generic tablet on the market.

“The purpose and effect of the 2017 Agreement is to ensure that Endo, the gatekeeper to competition in the oxymorphone ER market, has every incentive to preserve Impax’s monopoly. By doing so, it eliminates any potential for oxymorphone ER competition, allowing Endo and Impax to share in the monopoly profits. As a result, patients have been denied the benefits of competition, forcing them and other purchasers to pay millions of dollars a year more for this medication,” the FTC complaint alleges.

The 2017 agreement between Endo and Impax arose from a breach of contract case relating to a patent settlement between the companies over Impax’s generic version of Opana ER, in which Endo paid Impax more than $112 million not to compete. In 2019, the FTC ruled that settlement was an illegal "pay-to-delay" agreement.

Both Endo and Amneal deny there was any effort to create a monopoly in their 2017 agreement.

“It is Endo’s position that the Agreement had no adverse impact on actual or potential competition. At the time of the Agreement, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration had asked Endo to withdraw reformulated Opana ER from the market for safety reasons and Endo had publicly announced its intention to comply with the FDA’s request,” Matthew Maletta, Endo’s Executive Vice President and Chief Legal Officer, said in a statement to PNN.

“Significantly, as Endo has explained to the FTC, the Company has not launched or licensed any new opioid product(s) since that time, and the FTC’s theory that Endo would do so in the current litigation environment but for the Agreement is preposterous.”

“Far from being anticompetitive, the 2017 Amendment resolved a dispute between the parties that could have kept Impax's lower-priced generic product off the market entirely,” Amneal said in a statement. “We are confident there is no unlawful restraint in the 2017 Amendment, because nothing in the agreement prevents Endo from competing, and we intend to vigorously defend against the FTC’s claims.”

The FTC decision to sue Endo and Amneal a second time was approved on a split 3 to 2 vote by the agency’s commission. The complaint seeks monetary relief and a permanent injunction to prohibit the companies from engaging in similar conduct.

Extended-released oxymorphone is approved for the treatment of moderate to severe pain.