Arachnoiditis: My Not-So-Rare Disease

/By Julie Titone

I first heard the word “arachnoiditis” from the spine surgeon who performed my lumbar fusion. This was a virtual office visit. I leaned into my laptop screen to say: “That sounds like a spider.”

“Yes,” he replied.

He had identified the source of my unexpected post-op pain: arachnoiditis, a chronic inflammatory disease that’s even creepier than it sounds. Its symptoms usually arise after spinal trauma due to surgery, injury or commonly prescribed injections.

More doctors and patients should know about this small chance of a very big problem.

Arachnoiditis is so far incurable, difficult to treat, and can get worse over time. Patients experience lower body numbness and stinging pain that, at its worst, is likened to hot water dripping down the legs. The disease can lead to paralysis and bladder dysfunction. While arachnoiditis is said to be rare, it could simply be under-diagnosed.

The arachnoid is a membrane with a webbed appearance, hence its spidery name. It is part of the sheath that encloses the spinal fluid. Arachnoiditis is the inflammation of that easily annoyed membrane.

Sometimes it causes free-floating spinal nerves to stick together and become locked down by scar tissue. This is known as adhesive arachnoiditis, the kind I’m describing here.

No one knows how many spinal surgeries result in arachnoiditis, but a common estimate is 3 to 6 percent. Propelled in part by the deteriorating backs of boomers like me, there were more than 340,000 such surgeries in 2023 in the United States.

Just 4% of that adds up to 13,600 people suffering from arachnoiditis in a single year in a single country. The number doesn’t include cases that emerge after spinal injections of anesthesia or steroids, or after accidents that damage the spine.

‘They Stuck Me Eight Times’

Sara Lewis was a young Florida nurse when, on New Year’s Eve in 2008, she required an emergency Caesarean section. Attempts to give her anesthesia before the surgery did not go well.

“They stuck me eight times to get the spinal block in,” she recalled.

Lewis left the hospital with a baby boy and excruciating pain. She went back to work, eventually switching to a less-demanding job. By 2014, she couldn’t work at all and didn’t yet have a proper diagnosis. By 2017, she had qualified for disability benefits. Lewis is only 44.

Many women choose epidurals to ease pain during normal vaginal deliveries. Unlike a spinal block, an epidural delivers anesthesia in a space outside the spinal fluid sac. Even that approach poses risk when done poorly.

Arachnoiditis sufferer Steve Lovelace would like women to consider that pain relief during childbirth might not be worth risking a lifetime of suffering. “I know so many women who have children and are in so much pain during what should be the most joyful part of their life,” he said.

Lovelace’s agony started with a freak tree-cutting accident in 1982 on an Oklahoma family farm. His 20-year-old torso was crushed, causing debilitating injuries that required multiple surgeries.

Now 63 and medically retired from a radiology career, the pioneering para-triathlete has teamed up with Lewis to create the YouTube podcast Arachnoiditis Unfiltered. Given what they endure, they are remarkably chipper co-hosts. Their goals: awareness, prevention and a cure.

Lori Verton aims for those goals, too. Verton lives near Ontario, Canada. In 1999, she was driving out into the dark on a mission to buy milk for her kids. She was injured when her car hit a deer. When her whiplash symptoms didn’t improve, her doctor ordered a spinal tap.

“While I was on the table, I felt my left thigh go numb, my left foot drop, I was incontinent. I knew immediately something was wrong,” she recalled. “They said, ‘We’ve bruised some nerves, it will heal.’”

Heal it did not. She was increasingly disabled by pain and estimates it took five years and a dozen doctors to diagnose arachnoiditis. Largely bedridden at age 42, she went on disability. Having worked as a physiologist and medical researcher, Verton pondered how to put her skills to use. That led to the creation of the Arachnoiditis and Chronic Meningitis Collaborative Research Network.

‘No One Knew Anything About It’

Forrest Tennant, a retired physician, is widely associated with arachnoiditis. The disease is the focus of his small foundation and Arachnoiditis Hope website.

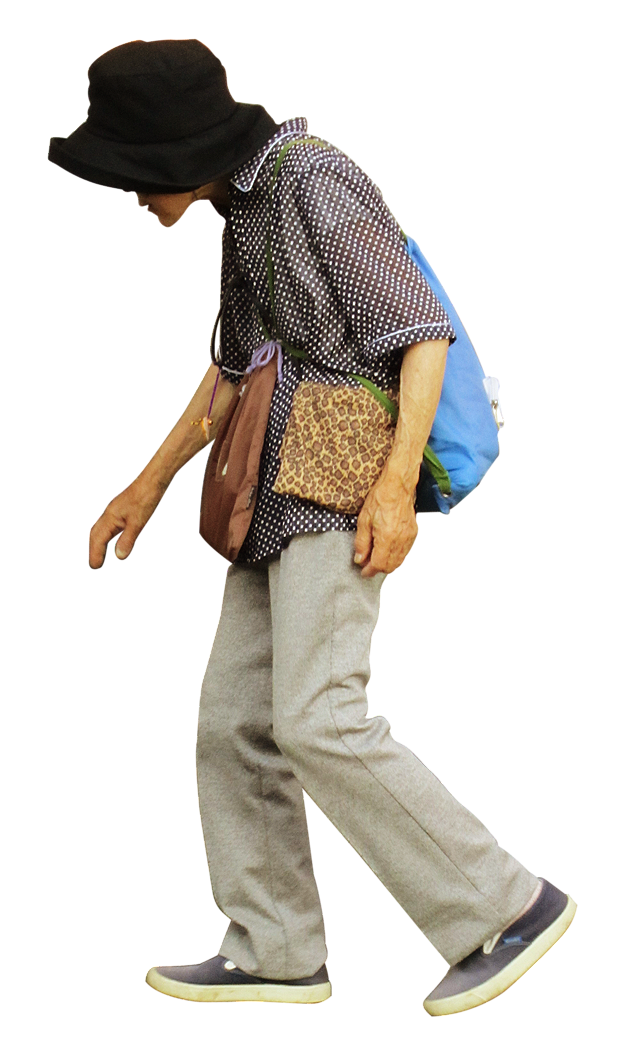

I watched a video in which Dr. Tennant said one hallmark of arachnoiditis patients is they are always moving. I thought: Ah, he knows us. With pain focused on lower backs, buttocks and legs, many arachnoiditis patients can’t sit comfortably. Nor, if they can stand, can they stay in one spot for long. Some can barely sleep.

I asked Dr. Tennant what spurred his interest in the disease. He said it was the number of people with the same symptoms who were coming into his pain clinic, and the high suicide rate among them.

“I found out no one was interested in the disease, no one knew anything about it. Patients were so grateful for any help they could get,” he told me.

Dr. Tennant said doctors from around the world contact him, seeking treatment advice. I don’t doubt it. I’ve read journal articles written by doctors from Poland, Brazil and China, scouring the medical literature for anything they can find on the subject. The authors of a recent case study described the literature on the disease as “vague and outdated.”

Dr. Tennant doesn’t dispute the value of injections for spinal pain, but said they can set people up for trouble, especially if they are repeated. He’s seen patients who had as many as 20 epidurals.

When we talked, I added up my own spinal intrusions. The first was a Caesarean. My preemie baby was arriving upside down and backward, so there seemed no alternative to spinal anesthesia there.

The second instance was a steroid injection aimed at reducing chronic pain that arose after hip replacement. It was a Hail Mary treatment that didn’t help.

Finally, in 2024, I had that single-level lumbar fusion. Four doctors had predicted dire health consequences if I didn’t get my spine reinforced. One physician confirmed my arachnoiditis diagnosis. As that surgeon was leaving the exam room he turned and said, “What would bother me is not knowing.”

In other words, not knowing why I developed arachnoiditis after my back surgery. Most patients don’t.

More Can Be Done

There’s a crying need for research into the causes of arachnoiditis. I find it hard to muster hope for significant advancement in the U.S., where federal health budgets have been slashed.

Still, there’s much that could be done to prevent and identify the disease. Medical schools could call attention to arachnoiditis as a possible cause of pain. Patients could be asked routinely about their history of spinal injections and counseled on the risks of doing more. All radiologists could be trained to spot arachnoiditis.

There could be a diagnostic code specific to the disease, making it easier to document and study. Spine surgeons, who know that arachnoiditis is consigning some patients to a lifetime of pain, could lead the charge to determine its cause.

Meanwhile, I’m depleted by stories like Matt’s. The 38-year-old Michigan man asked me not to share his last name, afraid that his disability could lead to job discrimination.

On July 18, 2023 – he’ll never forget the date – Matt was given steroid injections on both sides of a bulging disk. His back pain immediately increased. Then it spread. Now, he said, “I pretty much avoid doing everything else I used to do in my life, because it hurts.”

As I cope with arachnoiditis, I ponder how to spread the word about it. Maybe this disease needs a simpler name. It definitely could use a champion – so far, no celebrity has joined forces with arachnoiditis patients. If only Spiderman would come to our rescue.

Julie Titone is a former newspaper journalist who also worked in academic and library communications. She is retired and lives in Everett, Washington. Julie’s website is julietitone.weebly.com.

This column first appeared in her Substack blog and is republished with permission.