Medical Cannabis Saved My Life

/By Tammy Malone, Guest Columnist

People are talking about the addicts who are overdosing due to the opioid epidemic. Maybe we should start talking about the people who take opioids just to be able to function in life.

Chronic intractable pain is a terrible way to live. I know from experience that when you live in that much pain, you get to a point where all you can see is the ultimate way out. Chronic pain is blinding. It blinds you from life, family, joy and happiness. It robs you of your hopes and dreams, until you are left withering, suffering and asking yourself, "Is this all my life is ever going to consist of? Living in so much pain?"

Too many of us are forced to live this way. For some, it is just too much to bear and suicide is our only way out.

I can honestly say I have thought of this. I was in so much pain I was contemplating suicide. Then I found a compassionate, caring group of doctors at a Tennessee pain clinic and my life was spared. I was given shots, acupuncture, and massage. I started an anti-inflammatory diet that helps slow down the destruction of Lyme disease, which is breaking down the joints and bones in my body.

I was also put on a manageable dose of the opioid medication Demerol. For 6 years, I had my dreams back. I could see a future filled with family, friends, joy and happiness.

My body is still breaking down and nothing is going to change that. I'm 53 and have the spine of a 90 year old. I've shrunk over half an inch due to the discs deteriorating in my back. I've had 3 discs removed and my spine fused. Both knees are bone on bone. My hip joints have deteriorated and my shoulders are blown out. I have fluid pockets in many of the joints, so it's not only painful but difficult to move.

This destruction is not going to stop or get better, and I don't care how many Tylenol you throw at it, it won't touch the pain. But the pain management clinic helped me exist. The opioids helped me function and have a life beyond the blinding pain. It gave me another 2,372 days with my family and friends.

TAMMY MALONE

Then came the War on Opioids. My doctor discussed the issues this war was having on his practice and what it meant for his patients. What it was going to ultimately mean for me. To say I was in a panic is an understatement. The thought of returning to a life in that much pain was unfathomable.

I knew I had about 6 months before the do-gooders and Big Brother were going to push my doctor to start tapering me down. We discussed the other options, which we had or were already doing, and I cried. I knew what was coming. An unacceptable existence.

This was the same time my parents had talked about getting me and my husband a plane ticket to Montana for a mini-vacation at our family cabin in the Rockies. I really thought it was going to be my last family vacation. Because in a year, I wouldn't be around. Suicide was already in my forethought.

Although the stress of it all had begun to increase my pain levels, I agreed to go. The night I stepped off the plane, my ankles swelled to the size of my calves and I couldn't walk. In 11 days at the family cabin, I lost 22 pounds due to inflammation, elevation and the dryness of the mountain air. But I enjoyed the vacation and was happy I went.

I also learned that Montana was a medical marijuana state.

Over the next couple of weeks back home in Tennessee, I asked my entire team of doctors, seven in all, what they thought about medical cannabis. With the exception of my neurologist, they all agreed it might be an option. So we sold our dream property, got rid of our horses, sold everything in Tennessee and moved to Montana.

Starting Medical Cannabis

I'd like to say everything is 100% better, but that wouldn't be accurate. Moving to Montana and starting medical cannabis has been a challenge. After an incredibly stressful time of trying to find doctors who would even look at my medical records, I was able to find a compassionate doctor in Helena named Dr. Mark Ibsen. He went over my medical history, looked at my extensive list of medications, and reviewed my medical folders, MRI's and x-rays. After an hour of discussion, he agreed to take me on. I cried with relief. He was my lifeline.

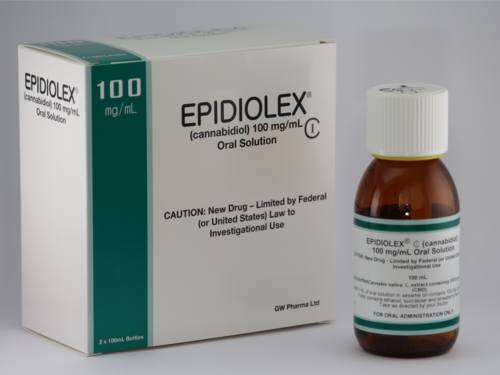

It took 6 months to taper me off my pain meds and reduce the other 44 pills I took everyday down to 7. Trying to find the right strain of medical cannabis hasn't been easy. I don't like to feel high or drugged (Demerol never made me feel that way), and finding the proper dosage of cannabis has been a challenge.

Cannabis doesn't relieve the pain completely. While Demerol kept the pain manageable at a 3-4 level, cannabis keeps me at a level 6, which is uncomfortable most days. Occasionally, when I overdo things, I can spend 24 to 36 hours at a level 8.5. Those are the days I wish I was still taking the opioids or at least had them as an option.

All in all, I was lucky. I was lucky my parents thought to give me a vacation that unexpectedly showed me there was another medical option. I was lucky my husband agreed that we should sell everything and try Montana. I was also lucky to find a compassionate doctor. It saved my life.

But I also think about all the other pain patients who do not have options. The "War on Opioids" has become a "War on Pain Patients." I did some research and found the opioid overdose numbers being publicized include all overdoses from heroin. These are addicts who are dying, not pain patients.

Not too long ago, I had a supposed friend call me an addict because she had preconceived idea of how I was living my life. That taking pain meds to function made me the same as her opioid-addicted son, someone who did whatever it took to get his fix. She hurt me and it cost a friendship, but it also made me see that too many of us are getting labeled.

Things need to change. We need to be heard and we need to tell our stories. We don't need to have people in Washington, DC leave us with suicide as the only option of living a pain free life. Too many of us are dying as it is. Please leave our pain management doctors alone as they are our lifeline to the future.

Tammy Malone lives with complex late-stage Lyme disease and Bartonella, a bacterial infection of the blood vessels. Both are spread by ticks. Tammy was first bitten by a tick in 2008.

The information in this column should not be considered as professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It is for informational purposes only and represents the author’s opinions alone. It does not inherently express or reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Pain News Network.