Medicare Pilot Program Could Deny Coverage of Pain Treatments

/By Grace Mackleby and Jeff Marr

Medicare has launched a six-year pilot program that could eventually transform access to health care for some of the millions of people across the U.S. who rely on it for their health insurance coverage.

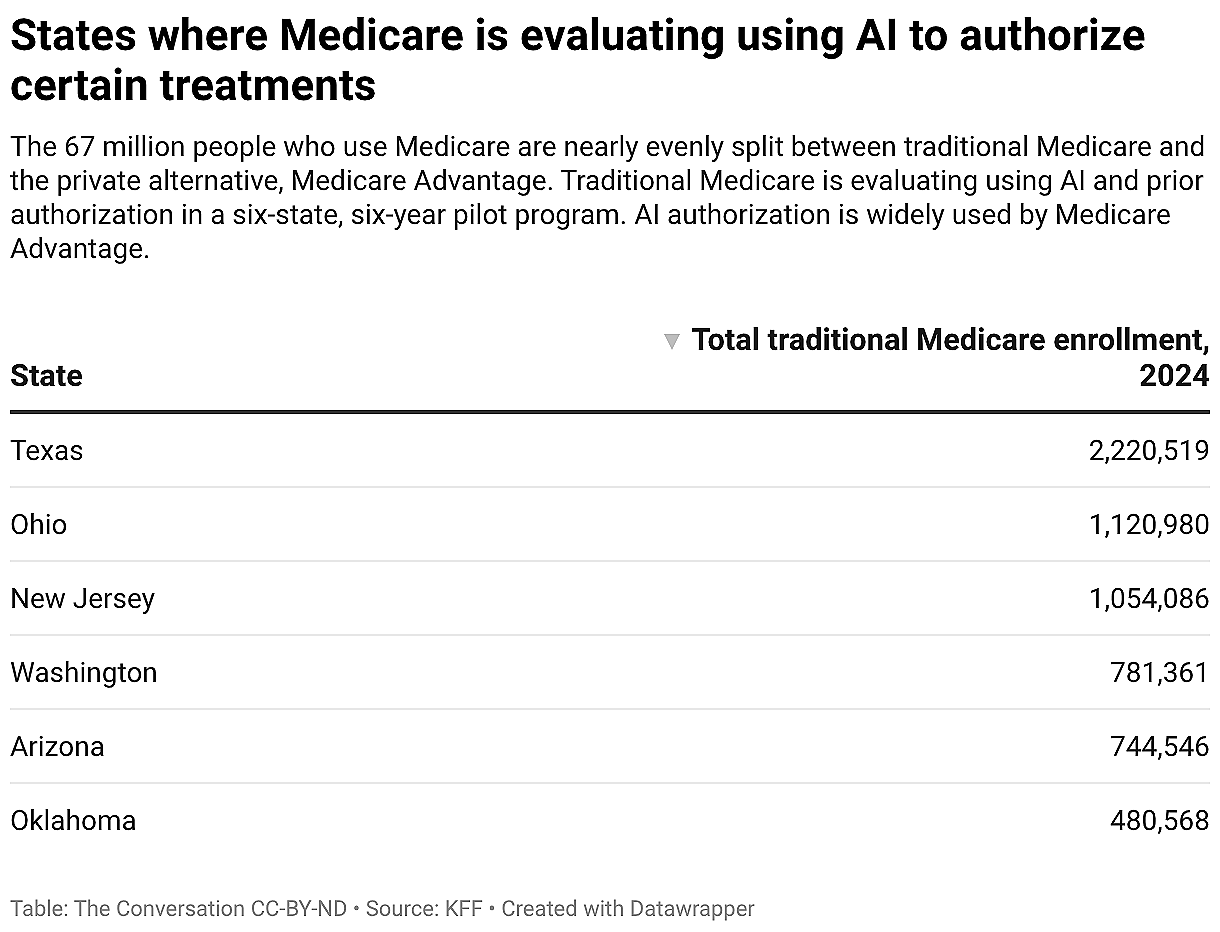

Traditional Medicare is a government-administered insurance plan for people over 65 or with disabilities. About half of the 67 million Americans insured through Medicare have this coverage. The rest have Medicare Advantage plans administered by private companies.

The pilot program, dubbed the Wasteful and Inappropriate Service Reduction Model, is an experimental program that began to affect people enrolled in traditional Medicare from six states in January 2026.

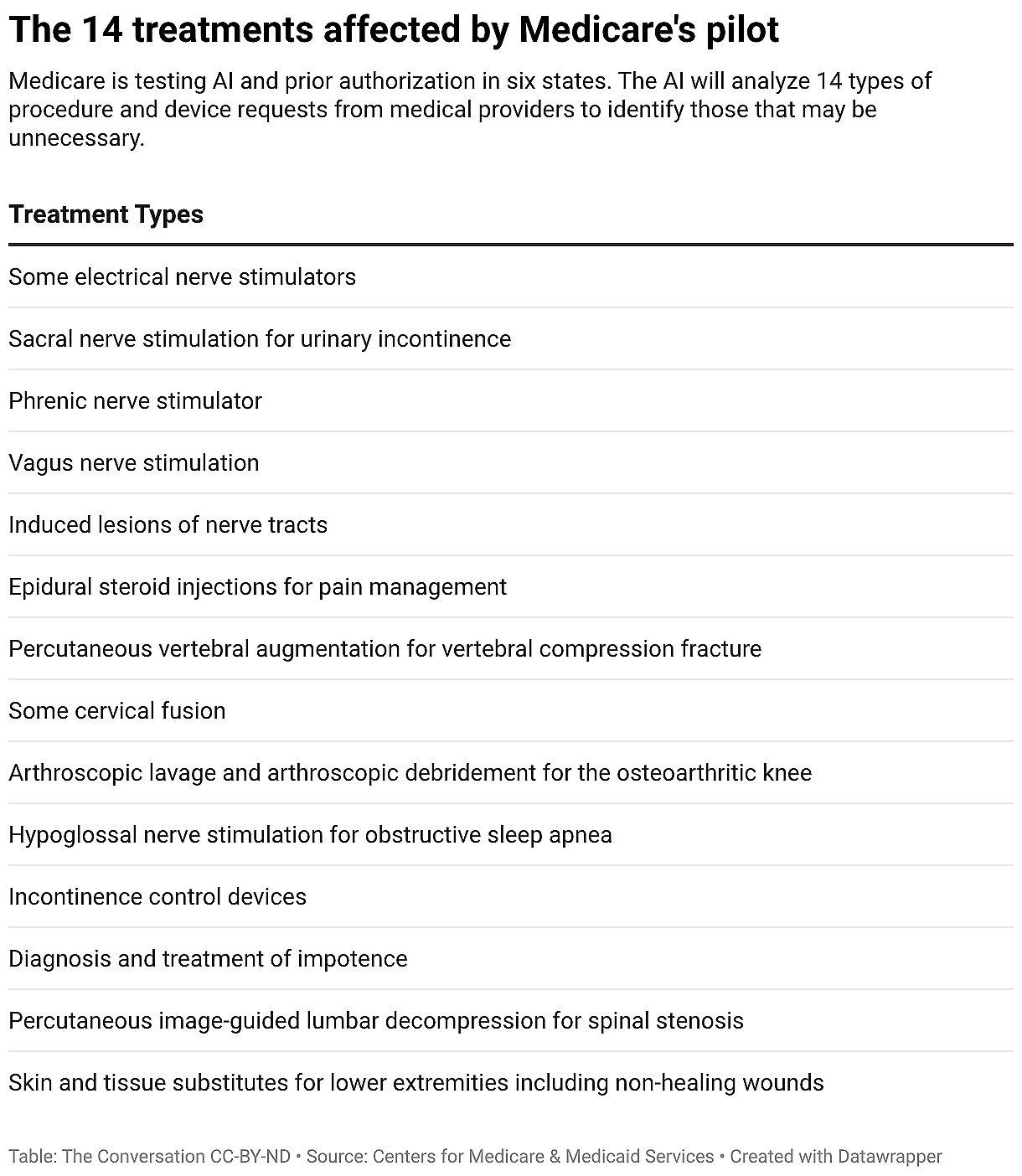

During this pilot, medical providers must apply for permission, or prior authorization, before giving 14 kinds of health procedures and devices. The program uses artificial intelligence software to identify treatment requests it deems unnecessary or harmful and denies them. This is similar to the way many Medicare Advantage plans work.

As health economists who have studied Medicare and the use of AI in prior authorization, we believe this pilot could save Medicare money, but it should be closely monitored to ensure that it does not harm the health of patients enrolled in the traditional Medicare program.

Prior Authorization Required

The pilot marks a dramatic change.

Unlike other types of health insurance, including Medicare Advantage, traditional Medicare generally does not require health care providers to submit requests for Medicare to authorize the treatments they recommend to patients.

Requiring prior authorization for these procedures and devices could reduce wasteful spending and help patients by steering them away from unnecessary treatments. However, there is a risk that it could also delay or interfere with some necessary care and add to the paperwork providers must contend with.

Prior authorization is widely used by Medicare Advantage plans. Many insurance companies hire technology firms to make prior authorization decisions for their Medicare Advantage plans.

Pilots are a key way that Medicare improves its services. Medicare tests changes on a small number of people or providers to see whether they should be implemented more broadly.

The six states participating are Arizona, New Jersey, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas and Washington. The 14 services that require prior authorization during this pilot include steroid injections for pain management and incontinence-control devices. The pilot ends December 2031.

If the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which administers Medicare, deems the pilot successful, the Department of Health and Human services could expand the program to include more procedures and more states.

An Extra Hurdle for Providers

This pilot isn’t changing the rules for what traditional Medicare covers. Instead, it adds an extra hurdle for medical providers before they can administer, for example, arthroscopic treatment for an osteoarthritic knee.

If Medicare issues a denial rather than authorizing the service, the patient goes without that treatment unless their provider files an appeal and prevails.

Medicare has hired tech companies to do the work of denying or approving prior authorization requests, with the aid of artificial intelligence.

Many of these are the same companies that do prior authorizations for Medicare Advantage plans.

The government pays the companies a percentage of what Medicare would have spent on the denied treatments. This means companies are paid more when they deny more prior authorization requests.

Medicare monitors the pilot program for inappropriate denials.

‘Low Value’ Treatments Targeted

Past research has shown that when insurers require prior authorization, the people they cover get fewer services. This pilot is likely to reduce treatments and Medicare spending, though how much remains unknown.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services chose the services targeted by the pilot because there is evidence they are given excessively in many cases.

If the program denies cases where a health service is inappropriate, or of “low value” for a patient’s health, people enrolled in traditional Medicare could benefit.

But for each treatment targeted by the pilot, there are some cases where that kind of health care is necessary.

If the program’s AI-based decision method has trouble identifying these necessary cases and denies them, people could lose access to care they need.

The pilot also adds to the paperwork that medical providers must do. Paperwork is already a major burden for providers and contributes to burnout.

AI’s Role

No matter how the government evaluates prior authorizations, we think this pilot is likely to reduce use of the targeted treatments.

The impact of using AI to evaluate these prior authorizations is unclear. AI could allow tech companies to automatically approve more cases, which could speed up decisions. However, companies could use time saved by AI to put more effort into having people review cases flagged by AI, which could increase denials.

Many private insurers already use AI for Medicare Advantage prior authorization decisions, although there has been limited research on these models, and little is known about how accurate AI is for this purpose.

What evidence there is suggests that AI-aided prior authorization leads to higher denial rates and larger reductions in health care use than when insurers make prior authorization decisions without using AI.

Winners and Losers

Any money the government saves during the pilot will depend on whether and how frequently these treatments are used inappropriately and how aggressively tech companies deny care.

In our view, this pilot will likely create winners and losers. Tech companies may benefit financially, though how much will depend on how big the treatment reductions are. But medical providers will have more paperwork to deal with and will get paid less if some of their Medicare requests are denied.

The impact on patients will depend on how well tech companies identify care that probably would be unnecessary and avoid denying care that is essential.

Taxpayers, who pay into Medicare during their working years, stand to benefit if the pilot can cut long-term Medicare costs, an important goal given Medicare’s growing budget crisis.

Like in Medicare Advantage, savings from prior authorization requirements in this pilot are split with private companies. Unlike in Medicare Advantage, however, this split is based on a fixed, observable percentage so that payments to private companies cannot exceed total savings, and the benefits of the program are easier for Medicare to quantify.

In our view, given the potential trade-offs, Medicare will need to evaluate the results of this pilot carefully before expanding it to more states – especially if it also expands the program to include services where unnecessary care is less common.

Grace Mackleby, PhD, is a research scientist of Health Policy and Economics at the University of Southern California. She is also a visiting scholar at the University of Utah Department of Population Health Sciences in Salt Lake City.

Jeff Marr, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Health Services, Policy, and Practice at Brown University. His current work focuses on Medicare, prior authorization, and the use of AI in healthcare.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation and is republished with permission.