Wear, Tear & Care: Recovering from Spinal Surgery

/By J.W. Kain, Columnist

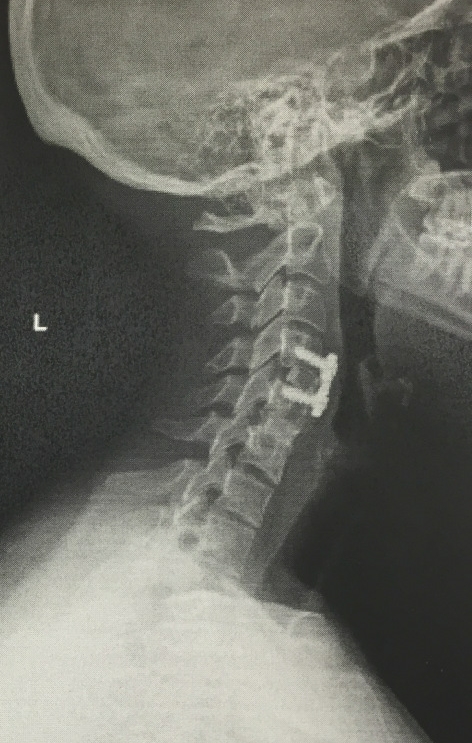

For those of you playing the home game (i.e. following my blog), I’ve been recuperating from a cervical discectomy and fusion of C4-C5. That was February 19. I’ve been recovering in an amazing fashion, much faster than my first fusion of C5-C6.

Just north of a month later, I also had thoracic injections at T-11 through L-1. I was far more scared of this procedure than the fusion -- and I’ve had injections before, so it was nothing new. I knew exactly what was going to happen, but I didn’t know how my body would react. Why? Read on.

My Abbreviated Back Story

My injuries have followed a strange road. When my mom’s car was stopped in traffic in 2004, we were rear-ended at 65 miles per hour. I was seventeen. I broke my spine in four places: T-11 through L-1, but also a facet joint that wasn’t found until a year later when it had calcified over a cluster of nerves. That’s why every movement in my midsection causes pain.

Nine years later, my car was rear-ended again. This led to my cervical and lumbar issues, the two fusions, and a frightful double-injury to my thoracic region. We haven’t touched that area since before the second accident because every procedure known to man (shy of surgery) had been attempted, and they generally don’t do surgery there unless you can’t walk. Plus, my neck was being very loud, so I had to deal with that before opening another can of worms. My doc decided to start at my head and work our way down from there.

My pain management doctor is incredible, amazing. Sympathetic, and smart as hell. Even so, in this current political climate and with the CDC’s asinine new guidelines, I have become afraid of the medical system in which I am firmly entrenched. Let’s discuss why.

This was taken mid-February. We’ve come quite a long way in a short amount of time. Now the hair is basically a pixie cut instead of the Furiosa.

The CDC Is Actively Harming Chronic Pain Patients

Normally I don’t write about the government. I don’t write about controversial issues because I don’t like arguing with people in the comments section. I didn’t write about the CDC releasing its opioid guidelines and how they glossed over chronic pain patients like we don’t exist. Before I get back to my thoracic injection story, here’s a blurb about why the CDC is so far off the mark that it hurts my heart.

One of my readers and I have been corresponding. After ages of complaining to doctors about intense, all-consuming pain, they discovered she had a tethered spinal cord -- as in, her head is essentially falling off her neck, according to the MRI report. Not only that, but those MRIs she’d fought to get, that her pain management doctor had said were “unnecessary,” revealed a host of other problems that will likely all merit surgery at multiple levels of her spine. The level of pain in which she lives is unholy. And now she -- and we -- have to fight for pain medication? We know our bodies. We know what works. And sometimes we have no other options.

The CDC should not have the power to take away a method of pain control upon which so many people rely without providing appropriate alternatives. You can’t tell someone who’s had to rely on Percocet for 30 years, “Oh, well, we’re taking those away now. We’ll wean you off those, refer you to physical therapy, and really get you into meditation.”

Meditation is great. Mindfulness is great. Yoga is great. Those alternative medicines are great. I use them all. However, they are great as a complement to medication. Sometimes medication is all we can use in order to actually thrive in this world and not just sit in a chair all day, every day, watching television and not able to function. We don’t want to have to apply for SSDI. We want to live. We want to contribute to society.

We don’t take opioids to get high. We take opioids to feel normal.

Back to Spinal Injections

Anyway. Rant aside, the fact that I have been in two car accidents, have literally thousands of pages of medical history to back me up, and have countless doctors who can verify structural damage, I am still afraid of not being believed. Pain is subjective. People are prone to exaggeration. We have to fend for ourselves unless we find that one-in-a-million doctor who can help and is not afraid of prescribing legitimate medication.

Look at the California doctor who was recently convicted of murder for overprescribing painkillers for clients. She was actually reckless in her actions, but her conviction echoed throughout the medical community. Many other doctors will now prefer to be hands-off entirely, leaving patients in the lurch.

my C4-C6 fusion

Thankfully, I have found the best pain management doctor at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. He understands that I am not just one big injury; I am a cluster of injuries at three different levels of my spine that were brought on by two separate car accidents. It doesn’t seem like it’d be difficult to grasp, but so many doctors didn’t believe that the second car accident -- much less drastic than the first -- could cause so much pain.

It wasn’t just the accident; it was the compounding of pain. I was already in pain and had been for nine years. This second accident created more pain. It’s a simple equation that many pain clinics somehow failed to grasp. Thankfully, my spine surgeon and my pain management doctor got me. They understood. They cared.

Which is why the thoracic injections were so horrifying. My brother was my designated ride, and after the procedure the nurses had to bring him back into the holding area because I was sobbing and on the brink of hysteria. (Naturally, in his haste he left my purse and coat in the waiting room, but he remembered all of his important stuff. Even in that state, I could see the humor of the situation.)

The pain of those thoracic injections -- an area that hasn’t been touched for probably eight years -- was so intense that I was literally screaming. These were diagnostic injections and a bit of steroid to see if the area was responsive after all this time. The doctormopoulos instructed the tech to give me a stress ball to squeeze and lots of tissues to drench. It took fewer than 10 minutes, but those 10 minutes were agony I have not felt before or since.

What if that had happened in front of a doctor I’d never met before? Somehow this was the same exact resident team that had done my lumbar injections a few months ago. Sometimes doctors switch up their accompanying residents, but nope -- we recognized one another. They saw the stark before-and-after versions of me.

What if that travesty were my first procedure? The new doctor would’ve stopped everything. We might not even have gotten to injections, because he might’ve glanced over my voluminous medical chart and said, “There’s nothing new to try, and they already did so much. This might be the best it gets for you.” And so many of us are told this!

Nobody sits you down after an accident and says, “You’re going to have chronic pain for the rest of your life.” It’s not like a cancer diagnosis when you only have so long to live. It’s always, “Well, at least you didn’t die!” We all think that we deserve to feel like we did before. We put our lives on hold because we think “I am going to get back to what I was. I’ll do the things I dreamed of doing... when I feel better.”

When I feel better. It’s always that thought in the back of our minds.

I finally realized that there might come a threshold where this is the best I get, and it won’t be close to what I used to be. Sometimes it’s not physically possible to be 100 percent again. If I can live a life that doesn’t just feel like “functioning,” like an automaton whirring my way through the day until I power down at night, then I will have succeeded. If I can do my job and contribute to society, I will have won. Then I think of all the patients who don’t have doctors they trust, who aren’t listened to, who aren’t taken seriously, and who aren’t believed.

In this new world of medical uncertainty, chronic illness patients need to form networks and advocacy groups. We need to share experiences with doctors. Was he understanding? Was she ready to help? Is their clinic’s position “deep breathing” instead of proper medication?

We need to participate, no matter how terrible we feel. In any capacity, in any way we can, we need to be our own advocates.

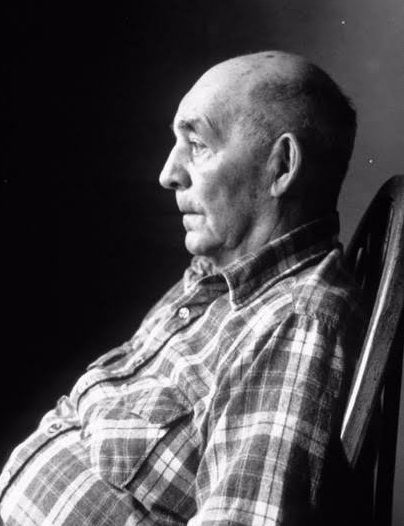

that's me. Makeup and non-pajamas for the first time in almost a month.

J. W. Kain is an attorney in the Greater Boston area who also works as a writer and editor in her spare time. She has chronic back and neck pain after two car accidents.

You can read more about J.W. on her blog, Wear, Tear, & Care.

The information in this column should not be considered as professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It is for informational purposes only and represents the author’s opinions alone. It does not inherently express or reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Pain News Network.