Maddening Advice: When the Dots Don’t Connect

/By Pat Akerberg, Columnist

If I didn’t have a neurological pain disorder that defies resolution, I would scream out loud in frustration. But talking and screaming are huge pain triggers, so I avoid them.

You might be thinking that I want to scream because of the hundreds of horrific electrical pain spikes I endure all over my skull every day. But that’s not actually why -- uninvited and uninformed advice are what makes me want to scream!

Not a day goes by that I don’t read some comment, hear of some off-the-mark advice offered, or field some intrusive advice myself. You know the kind.

It’s advice that’s given as if it holds the illumination of the brightest sage on the planet; and ought to be surrounded by a glowing halo. Forget that it doesn’t fit the whole picture – the complexity of my medical disorder, pain, history or my own experience.

Oftentimes the suggestions and advice come in the form of simplistic, sweeping generalizations, with a hint of judgment laced with a black and white attitude. If it worked for my aunt, then it will work for you – an improbable dot.

Sometimes it even comes with a hurled platitude or two for extra measure.

My personal non-favorite is the one that implies that we’re not given more than we can handle. The implication being that we just handle it then.

“Just” is another pesky diminishing, misguided dot.

What if the reality is that some days we can and others we can’t, hard as we try? Sometimes the right action in response to Yoda’s, “there’s no try, only do” is to not do.

And I marvel at the pull yourself up by your bootstraps, take charge, buck up, get happy, and do something to help yourself variety of advice. Chances are some version of that is usually offered by someone who either never has or only temporarily had to live with pain, and not of the disabling kind. It’s the kind of “tough love” pep talk more fitting for enablers to deliver to an addict.

But we’re not addicts; nor are we malingerers.

These one-way, one-size-fits-all approaches are not motivational, considerate, or even pertinent in most situations.

Is it so hard to believe that there are various physical activities, like exercise, cardio, yoga, bike riding, etc., that are simply too demanding to bear for some people with debilitating illnesses?

Contrary to the no-pain, no-gain notion, sometimes those very activities actually thwart improvement. I can personally attest to experiencing those setbacks, causing me to regretfully cancel my Y-membership.

To some, that translates to I am not trying hard enough and don’t want wellness bad enough. Or that I am weak, succumbing to defeat. I can’t imagine anyone thinking that a person would prefer to live an impaired life voluntarily. If I could get back to work, I’d be out the door in a heartbeat.

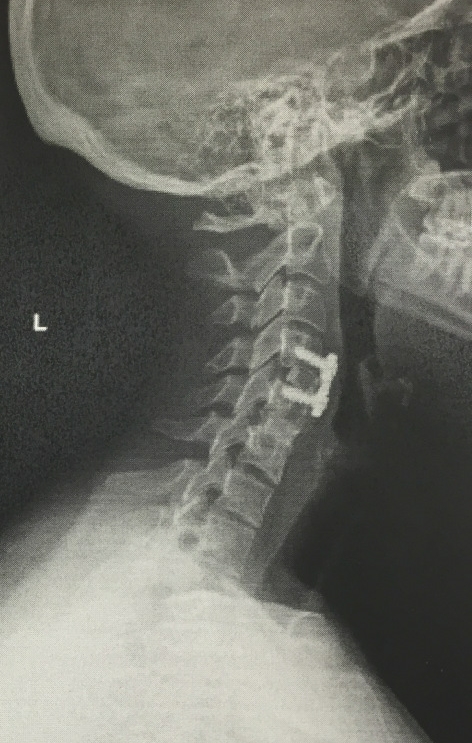

What if instead I know my own body, limitations, and my history better than someone else does? What if I’ve learned from a disastrous, damaging brain surgery how to pay keen attention to my gut instincts about potential harm?

A friend of mine calls that honing skill his “Spidey” sense. The best part is that you don’t have to be a super hero to have it either. I suspect a few of us have developed it the hard way.

Growth and development comes in many forms -- not always external in nature. Though we may not be exercising or running; there’s plenty of internal growth going on in will, courage and fortitude.

It’s how we carry on.

Then there are the obvious suggestions that test anemic up against the unrelenting pain wallops that resist much of what’s out there to abate them.

It might surprise some advice givers to learn that serious chronic pain sufferers laugh silly at the notion that Tylenol, Advil, a good vitamin complex, bottled water (yes, I was offered that one), a certain diet, or doing _______(fill in the blank) will relieve our pain.

You’ve probably heard others just as ill-fitting or absurd. None of those dots that plop can stop the neuropathic pain strikes relayed through my faulty central nervous system.

Once I heard a man tell other pain sufferers that they could not have possibly tried all of the potential pain treatment options out there, that no one could in their lifetime.

Some sufferers have researched and lived with their chronic conditions for years, have seen dozens of specialists in multiple states, had multiple surgical procedures, and/or have taken an untold morass of medications – all factors the advice giver couldn’t have known or considered.

I do realize that sometimes people, even well intentioned, just don’t know what to say to someone who is suffering endlessly.

But there’s actually no requirement that advice or suggestions be given, is there? Support, the kind that connects, can be conveyed in so many practical, helpful ways based on the person’s actual needs.

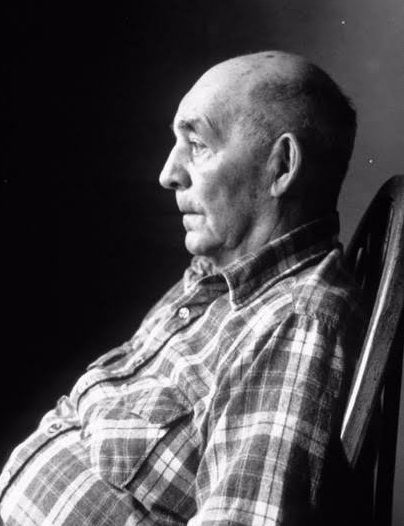

Often self and other awareness can go a long way during difficult circumstances. I mean the pause of “until you’ve walked a mile in my shoes” kind of other awareness. And the restraint of “err on the side of doing no harm” self awareness if you aren’t sure.

People in pain are often misunderstood, maligned, barely listened to, or believed. One of the greatest gifts someone can give to a chronic pain sufferer is their supportive presence. A caring friend or family member simply willing to listen is balm for the spirit.

In the end, self care trumps unsolicited, disconnected advice. Apparently today that involves tuning my Spidey advice radar up yet another notch.

Along with that comes the personal responsibility to do my best not to inflict the same unwanted practice on others.

Pat Akerberg lives in Florida. Pat is a member of the TNA Facial Pain Association and serves as a moderator for their online support forum. She is also a supporter of the Trigeminal Neuralgia Research Foundation.

The information in this column should not be considered as professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It is for informational purposes only and represents the author’s opinions alone. It does not inherently express or reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Pain News Network.