Poor Pain Treatment in ER Raises Risk of Opioid Misuse Later

/By Pat Anson

Patients with acute pain who are dissatisfied with their pain treatment in emergency departments are more likely to misuse opioids three months later, according to a new study. The findings are particularly true for black patients, who are more likely to be unhappy with their treatment and to be sent home without an opioid prescription.

“While a great deal of studies on opioid misuse focus on overprescribing, this study flips the script by showing that under-prescribing—or more precisely, ignoring a patient’s pain treatment preferences—can also lead to harmful outcomes, especially when patients are dissatisfied with their care,” said Max Jordan Nguemeni Tiako, MD, an assistant professor at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and lead author of the study in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

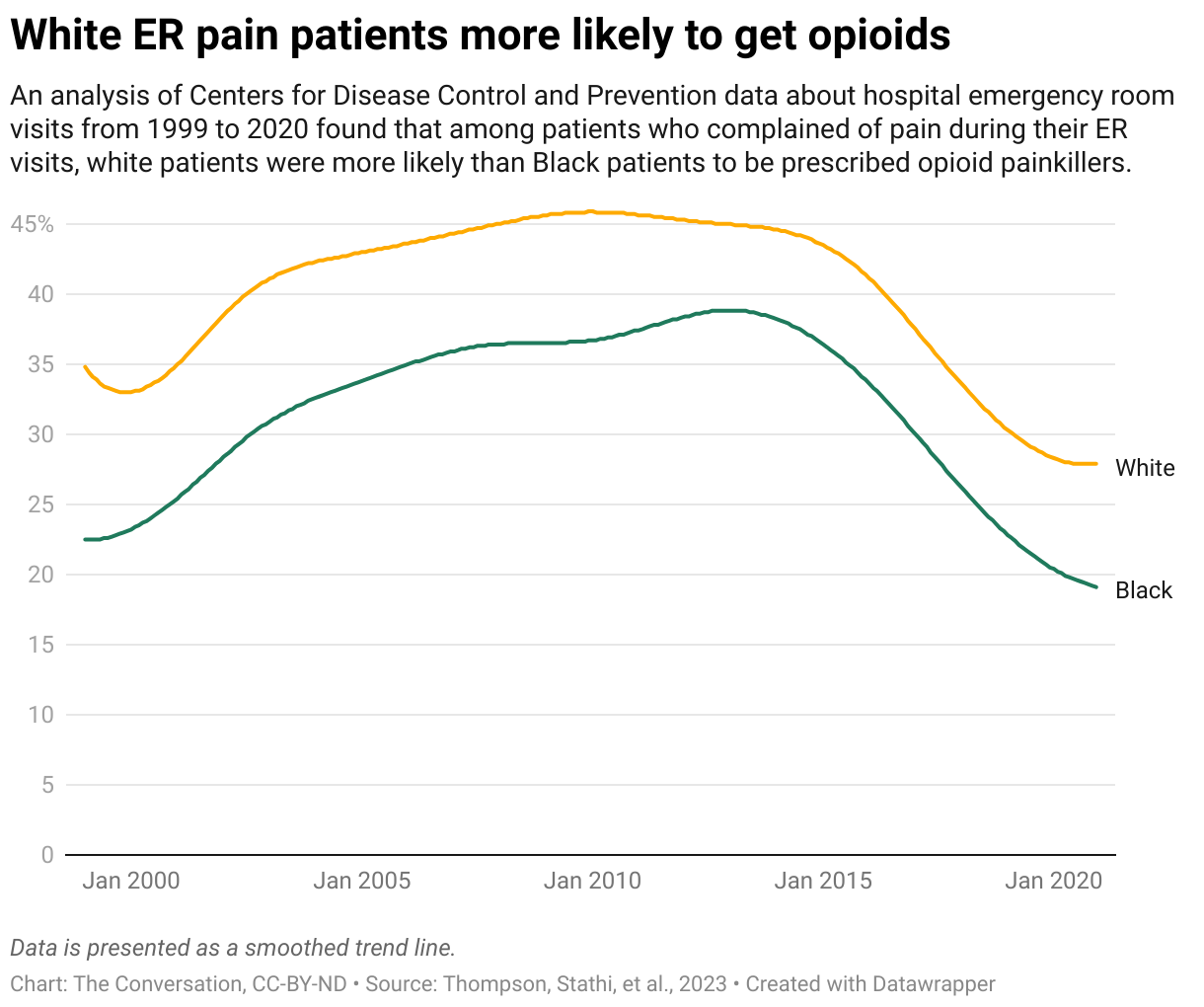

Previous studies have found disparities in pain treatment between white and black patients in emergency rooms, with white patients 26% more likely to get opioid medication. This new study has similar findings, but went a step further to see what the long-term consequences of poor treatment could be.

Nguemeni Tiako and his colleagues analyzed data for 735 ER patients treated for acute back or kidney stone pain, and surveyed them about their experiences 90 days later. The survey asked a series of questions about their medication use, appointment problems, emotional/psychiatric issues, and drug misuse --- and then assigned a current opioid misuse (COMM score) based on their answers.

Researchers found that black patients (21.8%) were more likely than white patients (15%) to have an “unmet opioid preference” when they were discharged from the ER. They were also more likely to be dissatisfied with their pain treatment overall.

Black patients with poor satisfaction and unmet opioid preferences had higher COMM scores compared to white patients. Both blacks and whites who were highly satisfied with their pain treatment had low risk of opioid misuse.

“The finding that unmet opioid preference had a unique effect on opioid misuse risk among Black participants is consistent with our prior analyses of this cohort, in which we found that receiving a prescription for opioids at discharge was associated with lower odds of reported non-prescribed opioid use,” researchers reported.

“Similarly novel to our study is the finding that satisfaction with pain treatment significantly mediates the impact of unmet preference on opioid misuse, especially among Black participants.”

While an unmet preference for opioids may lead some patients to seek relief through nonprescribed opioids, researchers think other factors in the ER could mitigate such risks, such as more empathy by providers, more patient-centered communication, and patient education about effective therapies and opioid risks.