Early Receipt of Opioids Reduces Hospitalization of Children with Sickle Cell Disease

/By Pat Anson

Early administration of opioids for pain relief in emergency departments significantly reduces the chances of a child with sickle cell disease being hospitalized, according to a large new study published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic disorder that causes red blood cells to form in a crescent or sickle shape, which creates painful blockages in blood vessels. About 100,000 Americans live with sickle cell disease, primarily people of African or Hispanic descent.

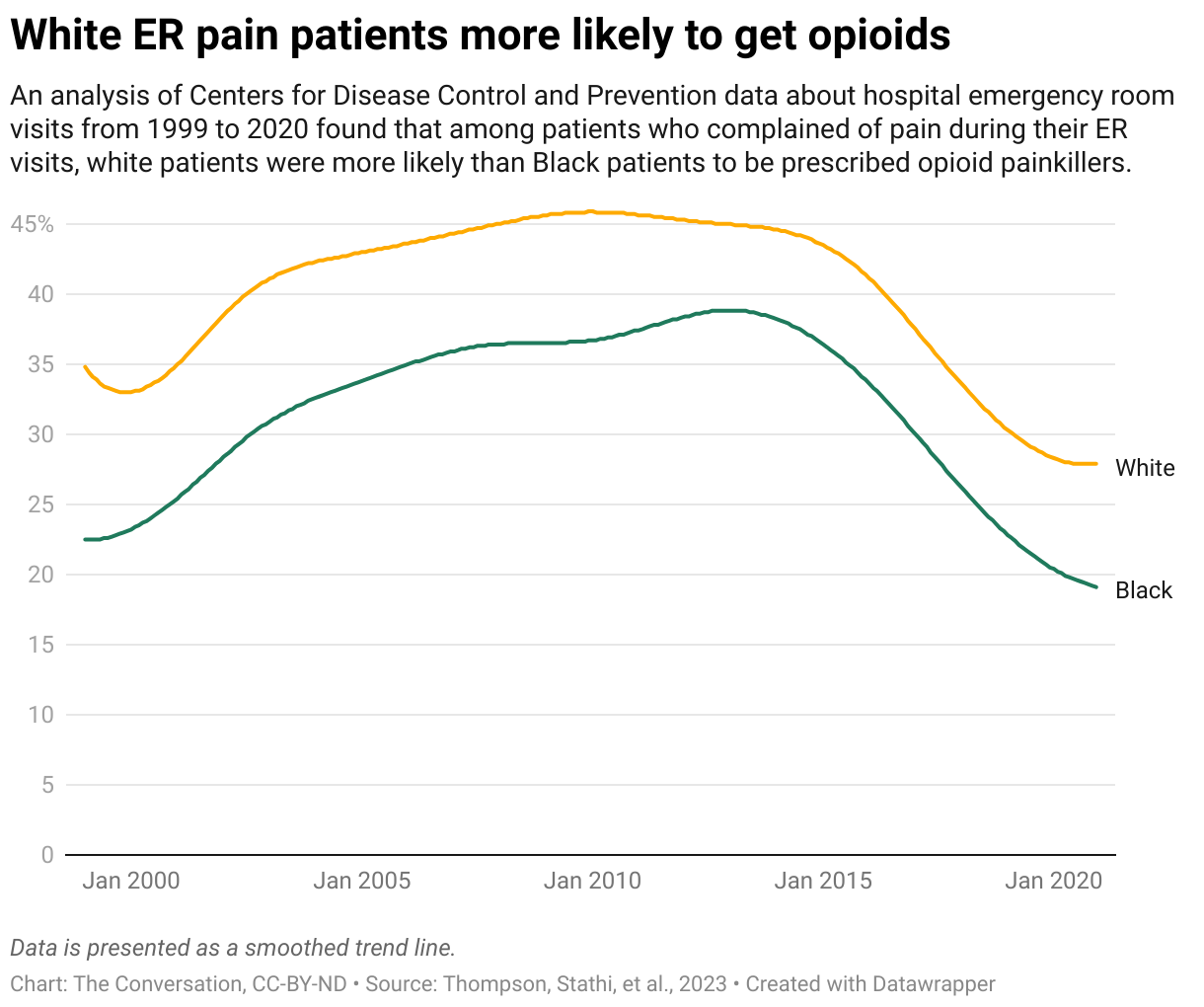

It’s not uncommon for someone with SCD to visit an ER a few times each year due to pain or complications such as anemia, stroke, infection and organ failure. Many patients with SCD feel stigmatized when they visit an ER, where their pain is not taken seriously and they are seen as drug seekers. That delays their treatment, even though medical guidelines recommend early treatment with opioids and other pain relievers.

“If we can stabilize and treat patients’ pain, they won’t need to be admitted to the hospital, where they would miss school, their families would miss work, and it’s disruptive to their lives,” said co-author Elizabeth Alpern, MD, Professor and Vice Chair in the Department of Pediatrics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

Alpern and her colleagues reviewed over 9,000 ER visits by 2,538 children with an uncomplicated SCD pain flare between 2019 and 2021. Their findings offer some of the first evidence that faster pain management with opioids can lead to better outcomes for pediatric SCD patients.

Children who received their first opioid dose within 60 minutes of arrival in the ER were 15% less likely to be hospitalized. The odds of hospitalization dropped even further when a second dose was administered within 30 minutes of the first.

“We were able to statistically show that if patients receive a timely first dose of opioid medications and a timely second dose of opioid medications, we could drastically reduce the number of hospital admissions within this population,” said co-author Jacqueline Corboy, MD, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics in the Division of Emergency Medicine at the Feinberg School of Medicine. “This is the first study that shows concrete evidence, so this is really important.”

The study was a collaborative effort among 12 pediatric hospitals. Two smaller, single-site studies showed no association between early receipt of opioids and lower odds of hospitalization.

SCD patients have few alternatives to opioids for pain relief. Last year Pfizer took the sickle cell medication Oxbryta off the market over concerns that it could be causing deaths and other complications. A 2022 study also found that SCD patients given corticosteroids are more likely to be hospitalized with severe pain.

Compared to other chronic illnesses, SCD has received little attention from researchers and pharmaceutical companies, resulting in a lag in the development of new treatments. Until 2018, only one drug was approved by the FDA to treat sickle cell patients. Bone marrow and stem cell transplants are currently the only curative therapies for SCD.