“A public health response to this crisis must focus on preventing new cases of opioid addiction, early identification of opioid-addicted individuals, and ensuring access to effective opioid addiction treatment, while at the same time continuing to safely meet the needs of patients experiencing pain,” wrote G. Caleb Alexander, MD, co-director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness at the Bloomberg School.

“It is widely recognized that a multi-pronged approach is needed to address the prescription opioid epidemic. A successful response to this problem will target the points along the spectrum of prescription drug production, distribution, prescribing, dispensing, use and treatment that can contribute to abuse; and offer opportunities to intervene for the purpose of preventing and treating misuse, abuse and overdose.”

The report calls on federal and state agencies, state medical boards and medical societies to require "mandatory tracking of pain, mood and function" at every patient visit, as well as patient contracts and urine drug tests. Patients prescribed high doses of opioids would be required to consult with a pain management specialist.

“It sounds like an aggressive government intrusion into the practice of medicine and is punitive towards providers willing to help people in pain. It certainly is a threat. Every physician in America should be concerned if these recommendations are adopted,” said Lynn Webster, MD, past President of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

“I am amazed that one of our finest educational institutions in America failed to address the source of the prescription drug abuse problem in their report. Not once did the report discuss the lack of safe effective treatments for pain. They almost totally ignored the needs of people in pain. Yet it is number one public health problem in America. Their focus was myopic and represents a narrow and prejudicial view of people in pain.”

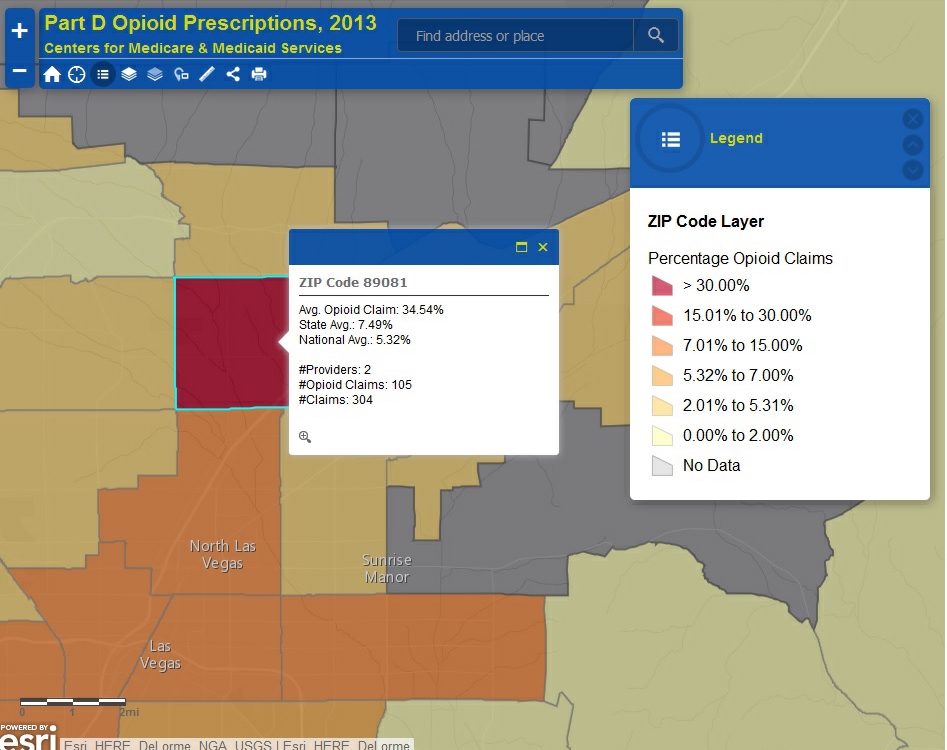

One of the more controversial recommendations in the report would expand access to prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) to private insurance companies and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). Access to those databases, which track prescriptions for opioids and other controlled substances, are currently restricted to regulators, law enforcement and physicians.

"It is a very bad idea to allow law enforcement or even payers to have access to PDMPs without a cause approved by a judge. This is personal medical information that should be protected," said Webster in an email to Pain News Network.

Under the Johns Hopkins plan, insurers would be encouraged to report suspicious prescribing activity to federal regulators and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

“Allowing managed care plans and PBMs access to PDMP data will improve upon their current controlled substances interventions that have been shown to positively influence controlled substances utilization,” the report states. “All PBMs should provide a list of suspicious pharmacies, prescribers and beneficiaries to the National Benefit Integrity Medicare Drug Integrity Contractor (MEDICs). Using the actionable PBM data they are receiving, MEDICs should be reporting potential providers for removal to the CMS.”

The report also calls for mandatory use of PDMPs by prescribers and pharmacies, more training for medical students in pain management, expanded federal funding of addiction treatment, and greater access to naloxone, a drug that can reverse the effect of an opioid overdose.

“What’s important about these recommendations is that they cover the entire supply chain, from training doctors to working with pharmacies and the pharmaceuticals themselves, as well as reducing demand by mobilizing communities and treating people addicted to opioids,” said Andrea Gielen, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Injury Research and Policy at the Bloomberg School and one of the report’s signatories.

“Not only are the recommendations comprehensive, they were developed with input from a wide range of stakeholders, and wherever possible draw from evidence-based research.”

One of the ”stakeholders” and a signatory of the Johns Hopkins report is Andrew Kolodny, MD, founder of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing (PROP), an advocacy group that seeks to end the overprescribing of opioids. Kolodny, who has collaborated with Dr. Alexander on other prescribing studies, is chief medical officer of Phoenix House, a non-profit that operates a chain of addiction treatment centers. According to a note on PROP's website, "PROP is a program of Phoenix House Foundation."

Kolodny has referred to opioid pain medication as “heroin pills” and has called for expanded access to buprenorphine, a weaker opioid widely used to treat both addiction and pain.

The Johns Hopkins report would greatly expand the use of buprenorphine by ending the 100 patient limit on the number of people that DEA licensed physicians can treat with buprenorphine at any one time. It would also require federally funded addiction treatment programs, such as those offered by Phoenix House, to allow patients access to buprenorphine.

Although praised by Kolodny and many addiction treatment specialists as a tool to wean addicts off opioids, some are fearful buprenorphine is already overprescribed and misused. Addicts have learned they can use buprenorphine to ease their withdrawal symptoms and some consider it more valuable than heroin as a street drug.

"The 100 patient limit is going to be lifted. It is going to create buprenorphine pill mills and increase the abuse of heroin. You will have more doctors getting the DEA exemption as they would not be subject to visit by DEA inspectors checking on the patient limit," said Percy Menzes, president of Assisted Recovery Centers of America, which operates four addiction treatment clinics in the St. Louis, Missouri area.

Over three million Americans with opioid addiction have been treated with buprenorphine. According to one estimate, about half of the buprenorphine obtained through legitimate prescriptions is either being diverted or used illicitly.