By Matthew Giarmo, PhD, Guest Columnist

1. Government Leaders Have a Choice

History may record one day that politicians and policymakers had a choice: They could champion the rights of 50 million Americans in chronic pain who desperately need a hero or they could be scorned for unnecessary cruelty and playing politics with people's pain.

The gathering storm is a backlash to the heightened regulatory and surveillance culture that has commandeered our nation’s healthcare system. It will not go unanswered. We no longer allow government into our bedrooms to police sexual behavior, gender identity and abortion rights. And we sure as hell will not allow government to spy on our doctors and medicine cabinets.

The government has blood on its hands from chronic pain patients resorting to suicide and street drugs after being abandoned by physicians who fear imprisonment by DEA agents who have no medical training or patient knowledge.

2. Opioids Misunderstood

Opioids are not only cheap; they are uniquely effective in restoring quality and functionality to millions of Americans who suffer from chronic or intractable pain. Opioid medication is safe when used properly, while long term use of ibuprofen and acetaminophen is toxic.

When we examine data on efficacy, toxicity, dependency, teen use, mortality and preventable causes of death, opioids do not warrant consideration as a threat to national health security. There is no opioid "crisis" or "epidemic."

I believe any determination to the contrary is a byproduct of inappropriate agency regulation (the 2016 CDC Opioid Guideline) and biased and conflicted advice from an extremist sect (Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing) operating at the fringes of the medical community. The growing realization among doctors and patients is that "the fools are in charge" and "the foxes are guarding the hen house.”

Inappropriate prescribing that resulted in spikes of opioid abuse, such as pill mills and dentists disposed to trade 60 Percocet for wisdom teeth, ended several years ago. So did the marketing of extended-release formulations like OxyContin.

3. Junk Science

You may have been seduced by contrived overdose statistics (“500,000 people died from an opioid overdose”) that remain viral, despite the CDC itself acknowledging that 48% of deaths due to illicit fentanyl were erroneously counted as deaths due to a prescription opioid.

When we break down the politically convenient and alarmist statistics into deaths involving polysubstance use, suicide, reckless dosing out of frustration with pain, and drugs that were never prescribed to the decedent, the 125 deaths per day initially claimed by the CDC looks more like 5 deaths a day.

It would be more appropriate to attribute these fatalities more to pain itself than to pain medication, as well as drug experimentation, depression or diversion. Most of those who abused OxyContin reported never having a valid script. That is no basis on which to separate chronic pain patients from their medication.

But as long as an opioid shows up in a post-mortem toxicology screen, deaths are being classified as an opioid overdose; even when the opioid was one of several drugs consumed, when it cannot be determined whether the opioid was consumed in a medically relevant way, and even when the decedent was hit by a bus.

The overdose numbers had to be gamed, which makes sense when you consider that in 70% of cases, rulings on causes of death are made before the toxicology data is even available. Especially when you consider that those sky-high opioid fatalities seem out of step with the low rates of dependency (6% for chronic pain patients, 0.7% for acute pain and less than 0.1% for post surgical pain).

As a social psychologist, government analyst and research critic, I have identified about a dozen ways the science of opioids has been corrupted for financial gain, professional survival or advancement, and in service of a political cause.

One example is the claim that “80% of heroin users first misused prescription opioids.” That canard was violently ripped from a SAMHSA report and is misleadingly used to imply that 4 in 5 patients prescribed painkillers eventually use heroin. On the contrary, less than 4% of prescription opioid users turn to heroin.

Incidentally, 67% of heroin addicts reported that their prior use of prescription painkillers had not occurred in the past year. Hardly seems like an irresistible urge to me.

4. Not Knowing When to Say When

Much like Sen. Joe McCarthy wreaked havoc on a nation with reckless claims about communist infiltrators, opioid McCarthyism is killing our most vulnerable and innocent populations -- veterans, senior citizens, persons with disabilities and the chronically ill.

Regulations complicate and delay the dispensing of legal scripts for these patients at the pharmacy, creating a "what's-it-gonna-be-this-time" syndrome in which patients endure a new burden every month.

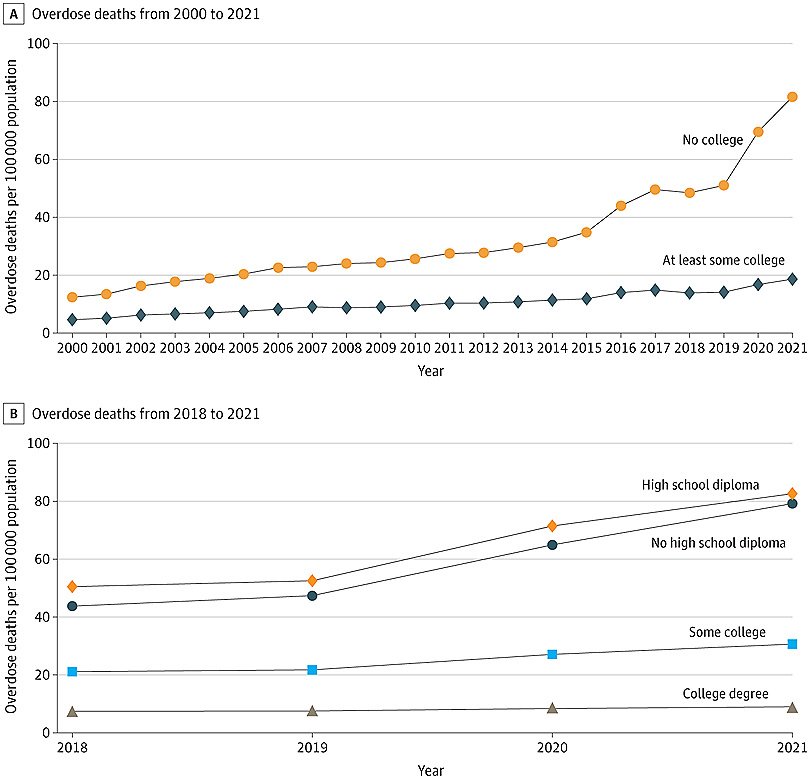

Prescriptions for opioid painkillers have declined 40% since 2011, while overdoses on heroin and illicit fentanyl have soared. As National Public Radio falsely reported that doctors are “still flooding the U.S. with opioid prescriptions,” solid research offers definitive evidence that prescriptive austerity is helping to drive the spike in overdose fatalities.

A recently published study found that among 113,000 patients on long-term opioid therapy, the incidence of a non-fatal overdose among those subjected to tapering was 68% higher than those who were not tapered. The incidence of a mental health crisis such as depression, anxiety or attempted suicide was 128% higher among those who were tapered.

5. The Inherent Absurdity of MME Thresholds

Forced tapering is undertaken to achieve an arbitrary one-size-fits-all threshold that makes no sense. There is no basis in science or nature for determining how much medication is too much. As long as patients are started at the lowest effective dose and titrated up gradually, as dictated by unresolved pain and any side effects, there is no limit to how much a patient might need 5, 10 or 15 years downstream.

Arbitrary dose limits defined in terms of morphine milligram equivalents (MME) ignore the importance of individual differences in medical diagnosis, treatment history (tolerance), and enzyme-mediated (genetic) sensitivity to pain and to pain medication. MME thresholds falsely assume that all opioids are equal and impact all patients the same way.

MMEs may be convenient for bureaucrats and expedient for politicians, but their scientific utility -- and by extension the CDC guideline itself -- is nullified by differences in the half-life of different drugs, differences in their absorption into the bloodstream, and differences in their rate of metabolism in different people.

6. Without Liberty or Justice for All

For arguments sake, let us suppose that we lose as many souls to prescription opioids as we do to car accidents. What have we done to rein in this other preventable cause of death? We create laws requiring safety belts, air bags, annual inspections, and compliance with speed limits. We do not criminalize the sale, operation and distribution of Honda Civics. We do not restrict the number of cars on the road. And we do not drop DEA teams behind enemy lines in Detroit.

But at a time when Americans are growing weary with a drug war that has lasted longer than our wars in Vietnam and Afghanistan -- and when Americans have softened their views on marijuana -- the DEA, perhaps in a desperate search for new bogeymen, expanded its theater of operations to treat pharmaceutical companies as drug cartels, doctors as dealers, and patients as addicts.

As we speak, your state is creating a mini-DEA inside its Department of Health or Medical Board that weaponizes the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program as a surveillance and detection tool, to spy on and red flag each patient and doctor whose script or “NARX Score” exceeds an arbitrary limit for which no basis in science or nature exists.

Think about all the sacred ideals we’ve abandoned to support our failed effort to bring a specious “opioid crisis” under control: the Constitution; a compassionate care system that had been the cornerstone of a civilization; a physician’s right to exercise clinical judgement; their right to due process; and a system of individualized, patient-centered care.

Government is obliged to ease civil unrest -- not foment it. But federal and state governments are hell bent on driving wedges between groups of stakeholders: physicians against patients; patients and physicians against pharmacists; patients against the public at large; physicians against their own office staffs; patients against employers; and physicians against medical boards. That is McCarthyism.

All too commonplace on social media are acrimonious altercations between the grieving survivors of overdose victims and those caring for friends or family living with chronic pain. There's no reason we can't simultaneously provide the medicine, assistance and requisite sympathy to Americans who need addiction treatment and Americans who need pain medication -- especially when we consider that only 6% of chronic pain patients prescribed painkillers develop dependency.

The NARX Score itself, a deeply flawed hotdog of a composite that ostensibly assigns a number to a person based on their supposed risk of overdose, is morally and intellectually offensive. It does little to assuage those who use the term “pain patient genocide" and compare it to the demonization and murder of 11 million Jews, gypsies, homosexuals and criminals in Germany during the Second World War.

7. Opioid Crisis As a Scapegoat

Have we as a nation become more addicted to the "opioid crisis" than we ever were to opioids? For our nation’s leaders, opioids have become an irresistible diversion and scapegoat. It’s a means to repair a tarnished reputation (see Chris Christie) or display rare bipartisan unity to disarm a cynical and frustrated constituency.

In a striking reversal of cause and effect, government officials would have you blame opioids for the loss of jobs, identities, finances and relationships that have come to define life in 21st century America. In reality, we have two crises: a crisis of chronic pain estimated to involve 50 million Americans and a psychosocial crisis linked to the combined effects of economic disparity, globalization, automation, immigration, social media, terrorism, pandemics, and the dissolution of national unity into political sects and interests.

Opioid critics like to point out that opioids only mask painful symptoms rather than address the underlying cause. But isn’t that what government officials do when they attempt to conceal or compensate for the true ills of our nation by playing whack-a-mole with prescription pain relievers?

8. The One-Track Mind

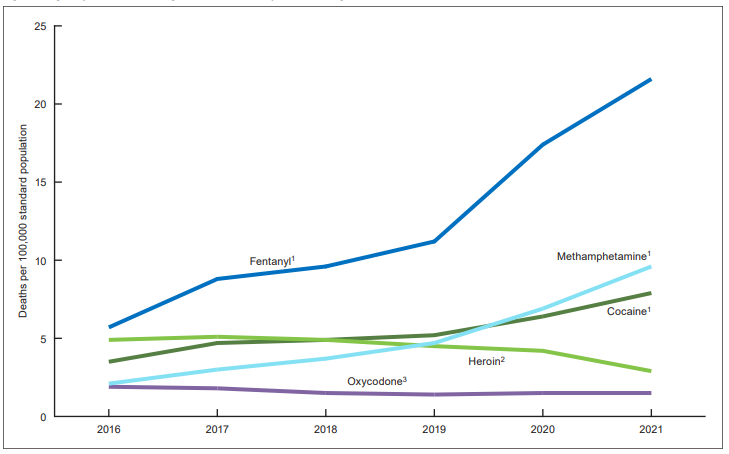

Last year a record 93,331 Americans died of a drug overdose, the vast majority involving illicit fentanyl and other street drugs, not prescription opioids.

We observed a 190% rise in cocaine overdoses and a 500% rise in overdoses involving methamphetamine. We have also seen increases in the abuse of alcohol and OTC substances like dextramorphan, diphenhydramine, ibuprofen, acetaminophen and loperamide, a drug used to treat diarrhea.

How many of those deaths can we blame on Purdue Pharma? Will collecting billions of dollars in settlement money from opioid distributors solve our overdose problem? Or will it enrich plaintiff law firms just like the Tobacco Settlement did?

9. An Unfair Fight

I was inspired to write this by a family -- MY family. I know what it’s like to see a patient’s treatment plan forcibly altered and how it affects not only the patient, but all those who cherish and depend on them. Children get less attention. Spouses assume a greater share of household responsibilities. Employers deal with lower productivity.

This memo and a lengthier report will go out to families and physicians across the country with the aid of hundreds of patient-advocate communities I mobilized on social media platforms. Still, it hardly seems like a fair fight. The meek of the Earth versus an army of federally funded Type A regulators and paid expert witnesses falling over one another to advance their careers and pad their bank accounts by making life harder for people to treat their pain.

10. Taking the Battle to the States

You may decide against reading my report, but you will likely hear about it from peers, co-workers or constituents in the months to come. It is making the rounds. State legislatures. Medical boards. Medical associations. Patient advocacy groups. Defense attorneys (I was twice asked to serve as an expert witness by physician counsel). Federal agencies.

In the past two weeks, my associates have disseminated my report to the American Medical Association, AARP, federal and state officials, members of Congress and the White House.

I invite readers to do the same by downloading my report, “There Is No Crisis.” We’re just getting started.

Matthew Giarmo, PhD, is a social psychologist who has worked with terminally ill cancer patients. Matthew authors research-based reports in social phenomena, including the impact on workforce development of the Software Revolution and Great Recession, and the degradation of science by professional and institutional requirements.