CDC Made Few Changes in Opioid Guidelines

/By Pat Anson, Editor

The Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) has made few changes in its draft guidelines for opioid prescribing, three months after they were widely criticized by pain patients and healthcare providers.

The agency still maintains that “non-pharmacological therapy” and non-opioid pain relievers are the “preferred” treatments for chronic pain, while admitting there is little evidence to support many of its recommendations. The guidelines also fail to address other issues, such as the lack of insurance coverage for many of the treatments the CDC advocates.

The proposed guidelines for primary care physicians were publicly released for the first time today as the CDC opened a 30-day public comment period on them. You can make a comment by clicking here.

The dozen guidelines can be found in a 56-page report, along with the reasoning behind them. You can see the report by clicking here.

“This guideline provides recommendations that are based on the best available evidence that was interpreted and informed by expert opinion. The clinical scientific evidence informing the recommendations is low in quality,” the report states.

“To inform future guideline development, more research is necessary to fill in critical evidence gaps. The evidence reviews forming the basis of this guideline clearly illustrate that there is much yet to be learned about the effectiveness, safety, and economic efficiency of long-term opioid therapy.”

The CDC was roundly criticized for the way it prepared and handled the initial release of the guidelines in September to a select online audience. The agency never made the guidelines available on its website or in any public form outside of the webinar, and only a 48-hour public comment period was allowed afterwards. The CDC also came under fire for secretly consulting with “experts” that included special interest groups and addiction treatment specialists, but few pain patients or pain physicians.

After getting feedback from critics, the CDC said it would make changes in its recommendations, but only a few changes can be found in the dozen guidelines released today:

1. Nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy are preferred for chronic pain. Providers should only consider adding opioid therapy if expected benefits for both pain and function are anticipated to outweigh risks to the patient.

2. Before starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, providers should establish treatment goals with all patients, including realistic goals for pain and function. Providers should not initiate opioid therapy without consideration of how therapy will be discontinued if unsuccessful. Providers should continue opioid therapy only if there is clinically meaningful improvement in pain and function that outweighs risks to patient safety.

3. Before starting and periodically during opioid therapy, providers should discuss with patients known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy and patient and provider responsibilities for managing therapy.

4. When starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, providers should prescribe immediate-release opioids instead of extended-release/long-acting (ER/LA) opioids.

5. When opioids are started, providers should prescribe the lowest effective dosage. Providers should use caution when prescribing opioids at any dosage, should implement additional precautions when increasing dosage to ≥50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME)/day, and should generally avoid increasing dosage to ≥90 MME/ day

6. Long-term opioid use often begins with treatment of acute pain. When opioids are used for acute pain, providers should prescribe the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids and should prescribe no greater quantity than needed for the expected duration of pain severe enough to require opioids. Three or fewer days usually will be sufficient for most nontraumatic pain not related to major surgery.

7. Providers should evaluate benefits and harms with patients within 1 to 4 weeks of starting opioid therapy for chronic pain or of dose escalation. Providers should evaluate benefits and harms of continued therapy with patients every 3 months or more frequently. If benefits do not outweigh harms of continued opioid therapy, providers should work with patients to reduce opioid dosage and to discontinue opioids.

8. Before starting and periodically during continuation of opioid therapy, providers should evaluate risk factors for opioid-related harms. Providers should incorporate into the management plan strategies to mitigate risk, including considering offering naloxone when factors that increase risk for opioid overdose, such as history of overdose, history of substance use disorder, or higher opioid dosages (≥50 MME), are present.

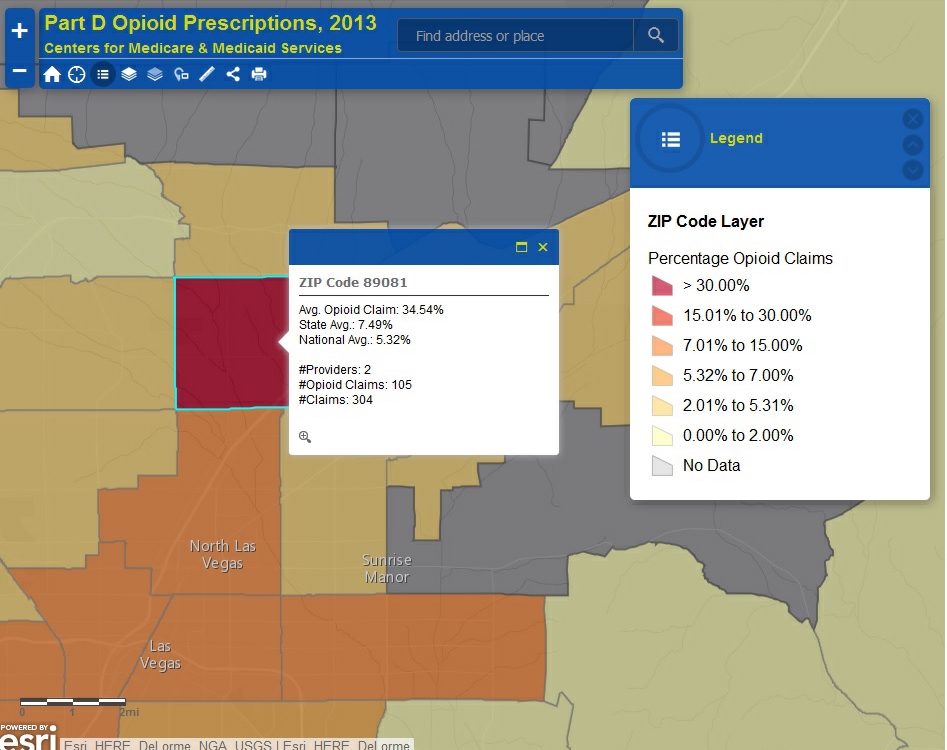

9. Providers should review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions using state prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) data to determine whether the patient is receiving high opioid dosages or dangerous combinations that put him or her at high risk for overdose. Providers should review PDMP data when starting opioid therapy for chronic pain and periodically during opioid therapy for chronic pain, ranging from every prescription to every 3 months.

10. When prescribing opioids for chronic pain, providers should use urine drug testing before starting opioid therapy and consider urine drug testing at least annually to assess for prescribed medications as well as other controlled prescription drugs and illicit drugs.

11. Providers should avoid prescribing opioid pain medication for patients receiving benzodiazepines whenever possible.

12. Providers should offer or arrange evidence-based treatment (usually medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine or methadone in combination with behavioral therapies) for patients with opioid use disorder.

Most of the dozen guidelines are strongly recommended by the CDC, even though the evidence used to support them was considered “limited” or there was “very limited confidence in the effect” of the recommendations.

Changes in Draft Guidelines

Some changes were made in guideline #5, which warns physicians to avoid giving patients high doses of opioids. The new guideline suggests that patients already taking high dosages “should be offered the opportunity to re-evaluate their continued use of opioids at high doses,” instead of having their medication abruptly changed to a lower dose.

However, no mention is made of a CYP450 genetic test, which can determine if a patient may need high doses of opioids.

“The CYP450 omission is disturbing since 20 percent of the population has some defect. How can you have a prescribing policy without CYP450 testing?” asked Gary Snook, a Montana man who needs extremely high doses of opioids to relieve pain from adhesive arachnoiditis. “It makes me wonder, are these doctors really qualified to put forth this draft that will have such an impact on so many that live in severe 24/7 pain? I think not!”

One significant change, in guideline #10, acknowledges that the results of urine drug tests are often wrong or misinterpreted. It recommends drug testing before opioid therapy begins and then annually, but random drug testing is discouraged. The guideline also recommends that providers not test for substances such as marijuana, which may not affect the efficacy of pain management.

If there are “unexpected results” from a urine drug test, the guideline says patients should not be terminated from a doctor’s practice, but should be counseled or offered treatment for substance abuse.

Pain Patients Urged to Comment

“I feel it's critical that members of the pain community, or people whose loved ones suffer from chronic pain, to take this rare second chance to refer to each of the guidelines and make their feelings known,” said Kim Miller, a pain patient and advocate..

“I feel it's important to keep your feelings out of comments to official government entities. Professionals are more receptive to calm remarks. There's no need to be inflammatory; other agencies, law firms, and numerous medical providers have already expressed their disappointment and disapproval of the previous draft guidelines. At this point, sticking to the facts is all that's necessary.”

The CDC is emphasizing the revised guidelines are voluntary and “intended to improve communication” between doctors and their patients.

Debra Houry, MD, the CDC official who oversaw development of the guidelines, even put out a Tweet, saying, “Patients & providers should decide together how to best treat long-term chronic pain.”

But critics say the guidelines, when adopted, could quickly become a standard of practice for state medical boards and professional healthcare societies, giving physicians little choice but to comply with them.

“These ‘guidelines’ are not looked at merely as suggestions,” Miller said. “When the CDC suggests there's no need for concern, after all these are only guidelines, it couldn't be further from the truth. The pain community must be sure to give these guidelines very serious consideration, your medical providers will be.”

After the public comment period ends, the CDC says the guidelines will be reviewed by a scientific advisory group, which will then appoint another working group to refine the guidelines further. The agency has not released a timetable or said if outside consultants who helped draft the initial guidelines will still be part of the process.

The CDC was criticized for consulting with five board members of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing (PROP), an advocacy group funded by Phoenix House, which runs a chain of addiction treatment centers. Critics say PROP has a conflict of interest when it advocates that pain patients be given greater access to addiction treatment.