She arrived in the room four mornings later to announce that not one place would accept me because I was “too complicated” due to my drug and food reactions. As a result, I was to be discharged to home. We were sent that afternoon to a motel that turned out to be filthy. I had to use a bedpan since I was no longer able to walk and then flew home the next day. It was humiliating and also dangerous to send me home just a few days after major surgeries, but we had nothing we could do to change this.

Lesson Learned: I did, in time, write to the president of the hospital to let him know how unacceptable this treatment was. From that point on, we were given a wonderful team to help make sure this never happened again. We have returned year after year to the same hospital for my surgeries.

Another event was dealing with IV’s. Because of my condition, IV’s were difficult to hold in place and many times became infiltrated, sending medication into the surrounding tissue instead of the blood stream. One night I kept telling the nurse in charge of me that the IV was dislodged. I was told all was just fine, even though as he administered the pain medication into the IV it stung and made the location of the injection swell immediately.

He said to “get some rest, you are just tired.” Well, I was right, the pain medication did not get into the blood. So, I had to suffer with unnecessary pain until an ICU nurse came down and was able to successfully get the IV catheter into a vein and stay there. This all happen in the middle of the night while I was in post op, exhausted and paying the price for a nurse not willing to listen to me and take me seriously.

Lesson Learned: Today, I no longer get an IV. We either use a PIC line or port for surgeries. They hold and work for me!

My next story involves a friend who was admitted to a hospital so sick that she was not able to get out of bed without passing out and going into seizures. Due to her complications, she was not able to get the care needed and was transported to Johns Hopkins Hospital. Within 24 hours, after a standard MRI while laying down, it was declared that she was to sit up, take the neck collar off, and be discharged.

The problem was the only way to get a true answer for what was wrong with her was to have an MRI while standing up.

After much hard work by her mom and husband, my friend was transported to Doctor’s Community Hospital; where it was determined, via the correct neurosurgeon who ordered the correct imaging, that she needed a neck fusion quickly to save her life. Yet, two hospitals wanted to discharge her home and felt she was just fine.

Lesson Learned: Be sure to get to a hospital that your skilled doctor has connections with. Don’t give up until you find the right doctor at the right hospital, for if my friend had listened to the first two places, she would not be alive today.

So what can we all do to change the potential of inappropriate treatment, or even no treatment at all?

1) Try to deal with your difficult issues, as much as you can, at home and with doctors you can trust, instead of running to a hospital. My husband and I have a pact to stay away from hospitals as much as we can to keep me safe, even though we both admit that we would so appreciate knowing we could go there safely for help.

2) If there is no choice but to go to the hospital, come as prepared as you can with files of your medical records, including lists of medications, medications you react to, supplements, diagnosis, previous surgeries, contact info for doctors that treat you, and tests done along with their dates and locations.

3) I have a packet of all this information that we keep in the car “just in case.” I also keep the records on my computer and can easily add new information when needed.

4) Make sure your doctor is part of the hospital you go to or is able to connect with the right people in the one you must get to.

5) If you have a negative experience, write the president of the hospital, not to just vent and complain, but with the intent to share issues of your care and to help educate in any way you can. Remember, if we just bad mouth them, we could potentially not be welcome at all. I had a phone call once from a local doctor who saw a negative Facebook post by a frustrated patient that included the doctor’s and the hospital’s names. The call was to ask me to take down the post, because the hospital staff were reading it and were really upset. The doctor told me we had to be careful how we dealt with this or people would reject taking us at all!

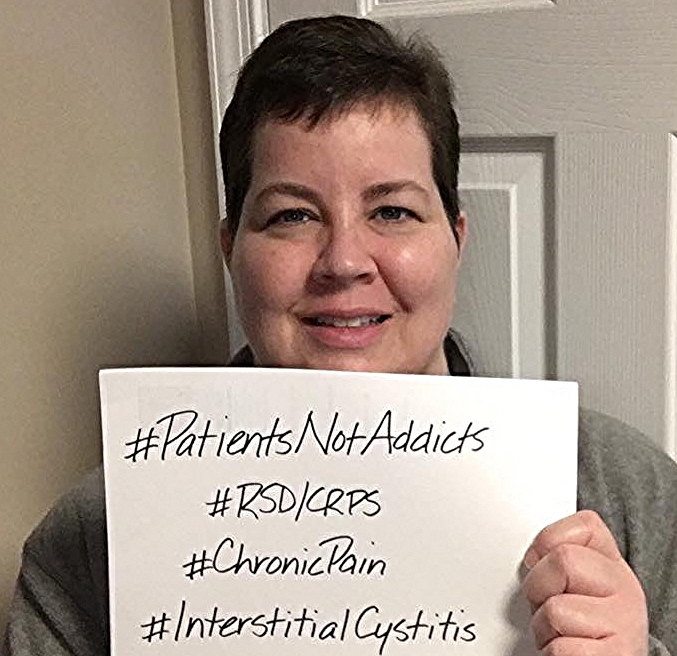

6) Write your congressman and share why being admitted to a hospital in their district is dangerous for you. If we don’t speak out, it continues and we suffer.

Unfortunately, we walk a fine line. We need to share these horror stories, but we have to be cautious how we do this. We want changes to happen, but we don’t want to turn people off by being so aggressive and so angry that they turn away from helping us or others like us in the future.

Education is constantly the theme; teach others what your condition is like, offer to speak out, and even consider a letter to the editor to share your concerns. But again, remember to think how you express these words. When somebody approaches you feeling extremely angry, you feel that vibration and want to back up. The medical team will feel this way too.

We have to be bigger people and put our anger aside to explain what it's like to be in our situation.