Stop Torturing Chronic Pain Patients

/By Kim Miller, Guest Columnist

Have you heard the stories about people who suffer from unrelenting pain?

These people, who we'll call "patients,” are trying to have a life whereby their pain is controlled enough to participate in some of life's little pleasures, such as cleaning the house, showering and spending time with family, while understanding that being completely pain free is unrealistic.

These patients are often treated as if they're asking for something unreasonable. They are not typical patients, but their anomalies have little place in the medical community, like other patients with chronic conditions such as hypertension or diabetes.

Chronic pain patients are typically required to visit their medical providers once each month if they are being treated with opioids. Along with these regular visits, chronic pain patients are subjected to signed contracts, random drug screens, reports from their state's Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (listing all scheduled medications, dates filled, names of pharmacies and prescribers' names), and random pill counts. Any failure to comply or meet with these specifications can result in the patient being released or "fired" by the medical practice for breaking the pain contract.

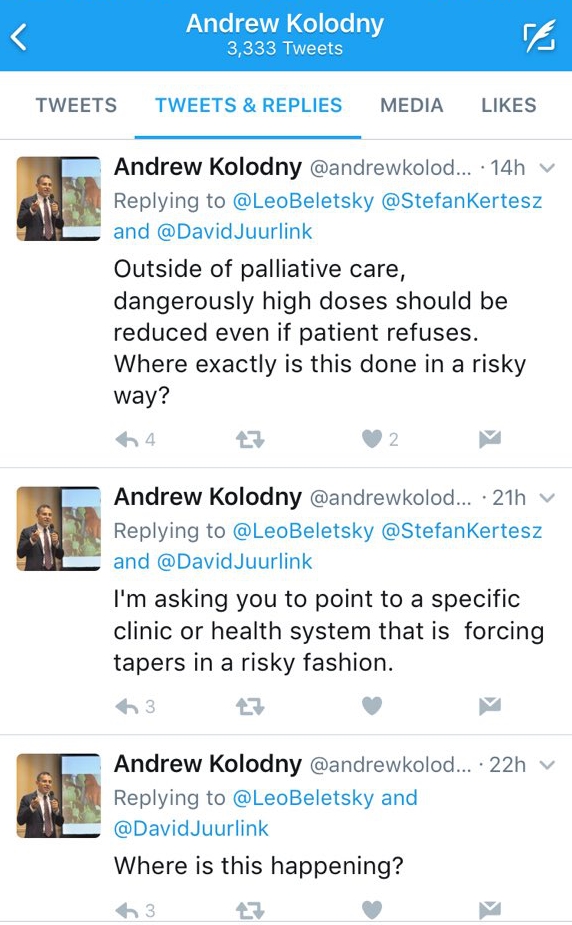

Many of these patients have been subjected to abrupt tapering of their opioid medications or had them completely discontinued.

The CDC opioid guidelines, the DEA, misinformed legislators, media hype, and anti-opioid zealots have combined to continually attack the nation's opioid crisis by restricting access to pain medications by legitimate, law abiding patients who are following all of the rules.

This process of restricting medications for patients in need has caused many to suffer needlessly and some to commit suicide. Even patients who have had no negative side effects from opioids -- after taking them for years or even decades -- are now suffering due to no fault of their own.

The worst part of the current situation is that overdose deaths caused by illicit opioids, such as heroin, street-manufactured fentanyl, and fentanyl analogs like carfentenil (elephant tranquilizer) and U-47700, continue to rise. Many media stories, as well as government reports and statements, do not differentiate between prescription opioids and illegal opioids when informing the public about the "opioid epidemic." The misinformed public only hears about opioids causing more deaths, while the picture on the television shows pills in a prescription bottle.

Restricting access to legal opioid medication has no hope whatsoever of curtailing what is an epidemic of non-prescription drugs.

The origins of the opioid crisis may have roots in the overprescribing of opioids, but a growing number of studies have found that opioid medications are no longer involved in the majority of fatal drug overdoses. Deaths categorized as "opioid related" often involve non-prescription opioids like heroin and illicit fentanyl, or benzodiazepines, alcohol, cocaine, methamphetamine and other substances.

The vast and overwhelming evidence points to dangerous substances NOT prescribed by a medical provider, yet we're left with continued restrictions on medications needed by pain patients to have any quality of life.

This dangerous counter-intuitive trend not only deprives patients of pain relief, but is leading to a silent epidemic of suicide in the pain community. It is time to rethink the media and political hype, ditch the CDC guidelines, and stop torturing chronic pain patients.

Kim Miller is the advocacy director of the Kentuckiana Fibromyalgia Support Group and an ambassador with the U.S. Pain Foundation.

The information in this column should not be considered as professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It is for informational purposes only and represents the author’s opinions alone. It does not inherently express or reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Pain News Network.