Illicit Use of Rx Opioids Down Significantly

/By Pat Anson

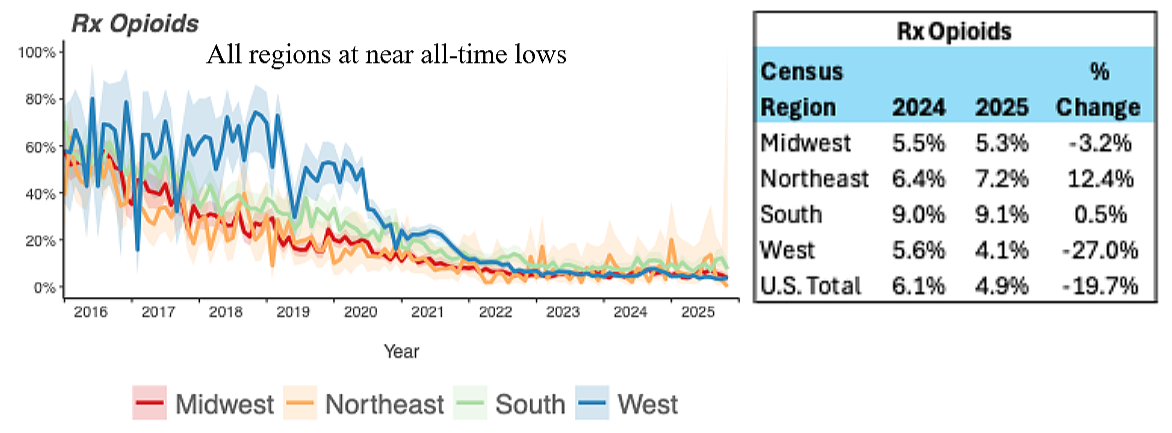

The illicit use of prescription opioids by patients undergoing addiction treatment has fallen dramatically over the past decade, according to a new analysis by Millennium Health.

The drug testing company analyzed nearly 1.7 million urine samples collected from patients diagnosed with substance use disorder (SUD). The findings show that opioid pain medication now plays only a minor role in the nation’s drug crisis, while the use of stimulants is growing.

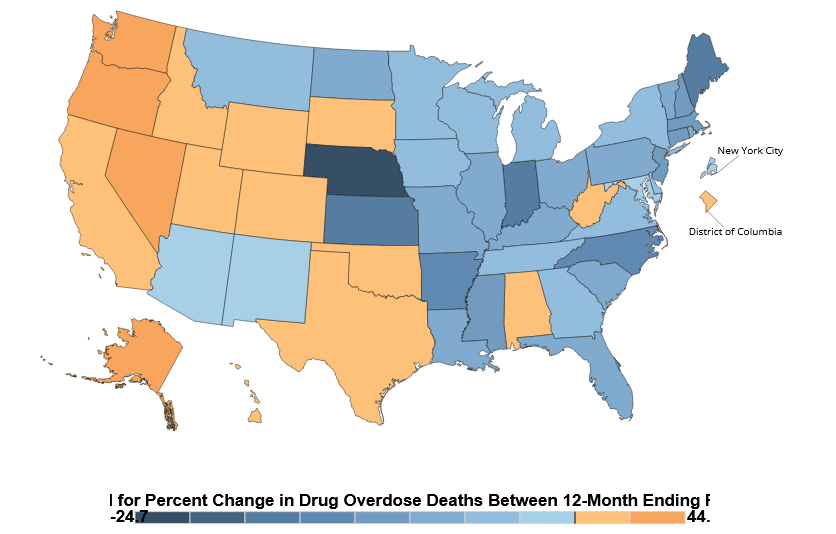

In 2016, up to 80% of the patients who tested positive for illicit fentanyl also tested positive for a prescription opioid that was not prescribed to them.

By 2025, only 4.9% of patients tested positive for both fentanyl and an illicit prescription opioid. There was a lot of regional variability in the numbers, with 9.1% of SUD patients in the South testing positive for both fentanyl and Rx opioids, compared to only 4.1% in the West.

Positive Drug Tests for Fentanyl and Prescription Opioids

SOURCE: MILLENNIUM HEALTH

“Within the population using fentanyl, we've seen a continued drop in the detection of prescription opioids in those using fentanyl. In 2025 the positivity rate for prescription opioids, I’m talking about hydrocodone, hydromorphone, oxycodone, oxymorphone, tramadol as a group, are at all-time lows in our database,” said Eric Dawson, PharmD, Vice President of Clinical Affairs at Millennium Health.

The findings suggest that fewer prescription opioids are being diverted into the illicit drug supply. That makes sense, as opioid prescribing has fallen sharply over the past decade and the medications are difficult for many pain patients to get. According to the DEA, the estimated diversion rates for hydrocodone (0.53%) and oxycodone (0.69%) in 2026 are both well under one percent.

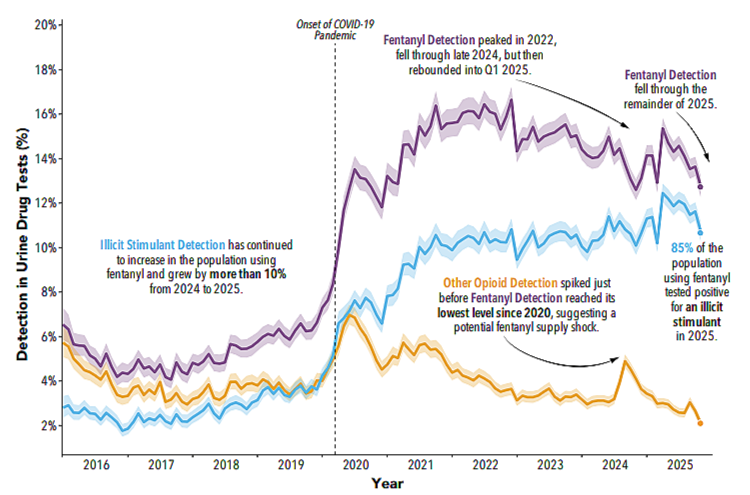

In their place, illicit drug users have increasingly turned to stimulants, such as methamphetamine and cocaine. Millennium’s data shows that while fentanyl and opioid use have declined in recent years, stimulant use has risen steadily.

Positive Drug Tests for Fentanyl, Opioids and Stimulants

SOURCE: MILLENNIUM HEALTH

“It makes us wonder if we're now moving to something more prominent, larger. I don't know the right word there, but a stimulant era,” Dawson told PNN.

“I continue to hear it everywhere I travel. Stimulants, methamphetamine and cocaine, are just incredibly plentiful in so many communities, and extremely inexpensive. And so, if you present a drug in front of a population that tends to use drugs and it's cheap or free and potent, they tend to gravitate toward that.”

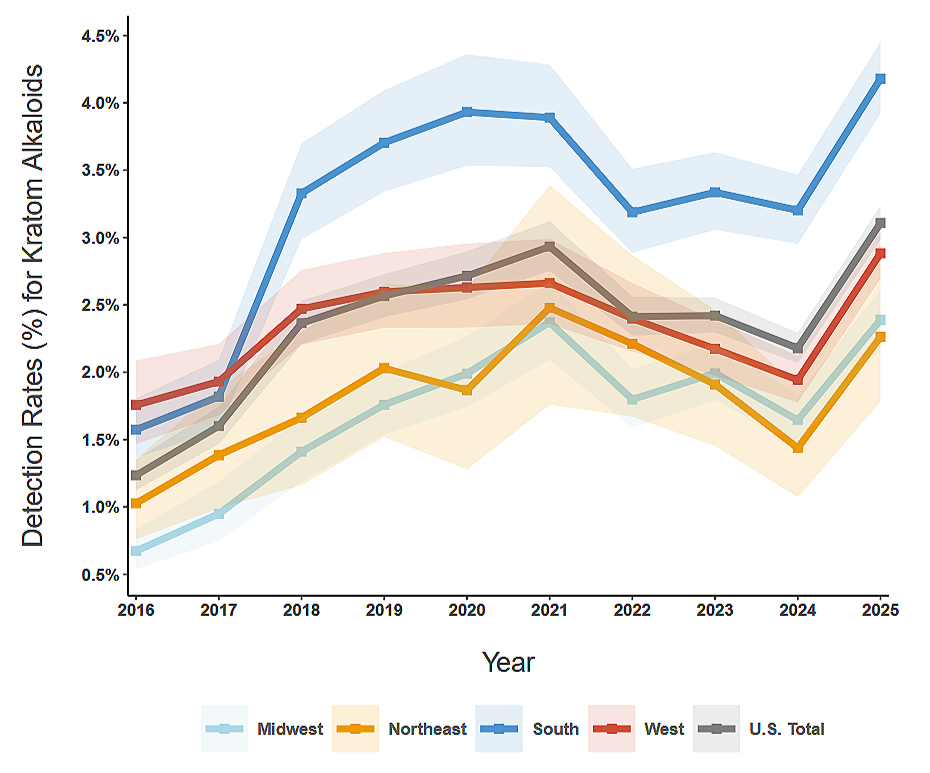

Another trend that appears in Millenium Health’s drug testing data is the growing detection of kratom and its alkaloids, mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine (7-OH).

In 2016, less than 1.5% of patients nationwide being treated for SUD tested positive for a kratom alkaloid. By 2025, that had grown to about 3 percent, with even higher levels in the South.

Positive Drug Tests for Kratom

SOURCE: MILLENNIUM HEALTH

Part of that growth can be attributed to the wider availability of kratom and increased awareness that the herbal supplement can be used to treat pain, anxiety and other health conditions.

The federal government estimates that 1.7 million Americans used kratom in 2021. The American Kratom Association, a kratom advocacy group, puts the number much higher, at 10 to16 million Americans.

The growing awareness about kratom has spread to addiction treatment providers. In 2016, only about a third of Millennium Health’s urine drug tests included a request from a provider to test for kratom. By 2025, over 77% of urine drug tests included an analysis for kratom.