Lack of Education Is Fueling Overdose Crisis

/By Pat Anson, PNN Editor

Anti-opioid activists have long claimed that excessive prescribing of opioids over a decade ago created an “epidemic of addiction” that lingers to this day. Once hooked on prescription opioids, patients turned to stronger and more lethal drugs — like heroin and illicit fentanyl — sending the overdose rate to record levels.

A large new study debunks that theory, showing that socioeconomic factors – particularly lack of education -- play a hidden but central role in the overdose crisis.

"The analysis shows that the opioid crisis increasingly has become a crisis involving Americans without any college education," said lead author David Powell, PhD, a senior economist at RAND, a nonprofit research organization. "The study suggests large and growing education disparities within all racial and ethnic groups --- disparities that have accelerated since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic."

Powell looked at data from the National Vital Statistics System from 2000 to 2021, and identified over 912,000 fatal overdoses for which there was education information on the people who died.

His findings, published in JAMA Health Forum, show that overdose deaths increased sharply among Americans without a college education and nearly doubled in recent years for those who don’t have a high school diploma. The findings are notable because they came during a period when per capita consumption of prescription opioids plummeted, sinking to levels last seen in 2000.

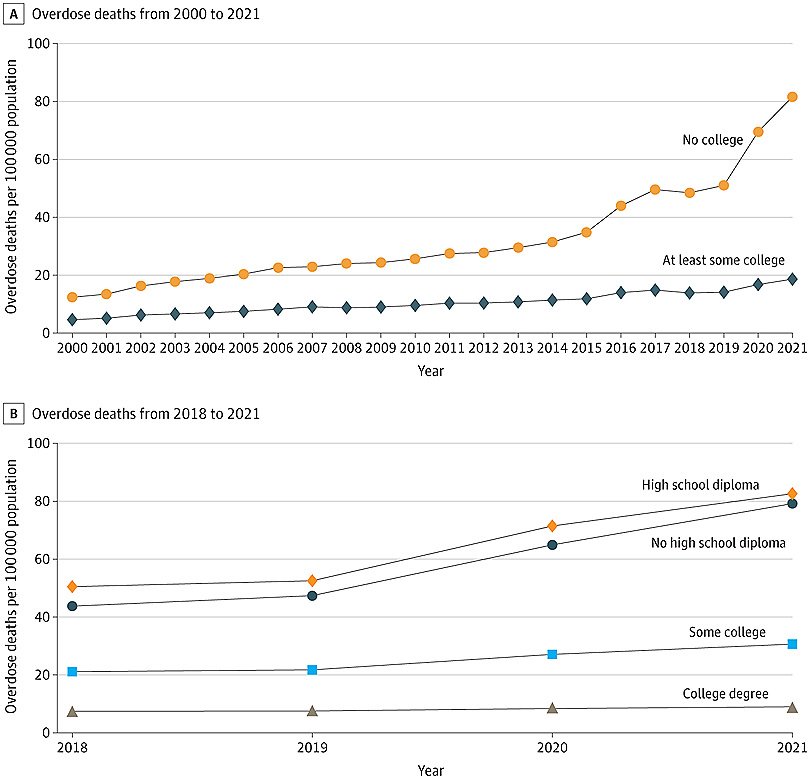

For people with no college education, the overdose death rate increased from 12 deaths per 100,000 individuals in 2000 to 82 deaths per 100,000 in 2021. That rate is sharply higher than Americans who have some college education. In 2000, their overdose rate was 4.6 deaths per 100,000 people, which rose to 18.6 deaths per 100,000 in 2021.

Trends in Overdose Deaths by Educational Attainment

JAMA HEALTH FORUM

Powell is not the first researcher to link socioeconomic factors to overdose deaths. The so-called “deaths of despair” were first reported in 2015 by Princeton researchers Angus Deaton and Anne Case, who found that economic, social and emotional stress were major factors in the reduced life expectancy of middle-aged white Americans, who increasingly turned to substance abuse to dull their physical and emotional pain.

Education plays a significant role in socioeconomic status. People without college degrees are more likely to have blue-collar jobs requiring manual labor, which raise the risk of work-related injuries and conditions such as arthritis. One recent study found that people who did not finish high school in West Virginia, Arkansas and Alabama were three times more likely to have joint pain compared to those with bachelor degrees in California, Nevada and Utah.

“Overall, the analysis suggests that the opioid crisis has increasingly become a crisis disproportionately impacting those without any college education. Research is needed to understand the driving forces behind this gradient, such as isolating the independent roles of differences in income, employment, family composition, health care access, and other factors,” said Powell.

“Overdose death rates grew during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the education gradient increased further, although it is unclear what role the pandemic had relative to changes in fentanyl penetration in illicit drug markets and other factors.”

Powell says education merits further attention in understanding how and why the opioid crisis continues to intensify and lower U.S. life-expectancy.