CDC: Fentanyl Urgent Public Health Problem

/By Pat Anson, Editor

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is finally acknowledging that the U.S. has a fentanyl problem that is growing worse by the day. And that more people are dying in some states from overdoses of illicit fentanyl than from prescription opioids.

“An urgent, collaborative public health and law enforcement response is needed to address the increasing problem of IMF (illicitly manufactured fentanyl) and fentanyl deaths,” CDC researcher Matthew Gladden, PhD, said in the agency’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

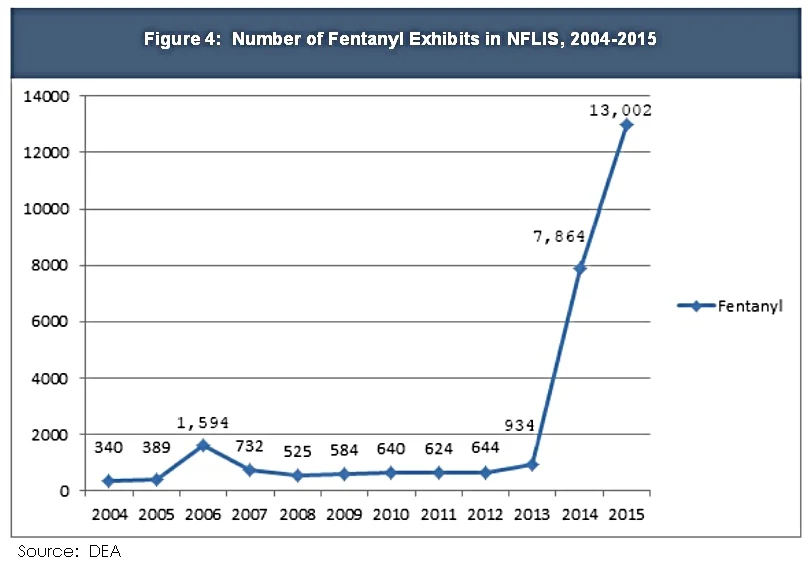

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine. It is prescribed legally in patches and lozenges to treat chronic pain, but in recent years there has been a surge in overdoses linked to illicit fentanyl obtained on the black market, where it is often mixed with heroin.

In a new analysis of opioid overdoses in 27 states, the CDC identified eight “high burden” states where fentanyl overdoses sharply increased, even though fentanyl prescriptions were relatively stable.

Those states are Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, Ohio, Florida, Kentucky, Maryland and North Carolina.

In six of the eight states, the CDC said fentanyl was the “primary driver” of synthetic opioid deaths – meaning they outnumbered overdoses from legal synthetic opioids. That is a major concession by the agency, which has long maintained that prescription opioids were primarily responsible for the nation’s so-called opioid epidemic.

The data analyzed was from 2013 and 2014. More recent reports from several states indicate the fentanyl problem has significantly worsened. The DEA recently reported the U.S. is being “inundated” with counterfeit prescription drugs made with fentanyl.

“This finding coupled with the strong correlation between fentanyl submissions (laboratory tests) and fentanyl-involved overdose deaths observed in Ohio and Florida and supported by this report likely indicate the problem of IMF is rapidly expanding,” Gladden wrote. “Recent (2016) seizures of large numbers of counterfeit pills containing IMF indicate that states where persons commonly use diverted prescription pills, including opioid pain relievers, might begin to experience increases in fentanyl deaths because many counterfeit pills are deceptively sold as and hard to distinguish from diverted opioid pain relievers.”

The CDC hasn’t been completely silent about the fentanyl problem. In October 2015 the agency issued a health advisory to public health departments, healthcare providers and medical examiners to be on the alert for fentanyl overdoses. Warnings to the public, however, have been scarce as the agency focused instead on controversial guidelines that discourage doctors from prescribing opioids for chronic pain.

Even the U.S. Surgeon General appears to be neglecting the fentanyl problem. This week Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, said he would be sending letters to over two million physicians urging them to follow the CDC guidelines and pledge to safely prescribe opioids. Nowhere in the letter or on a website promoting the “Turn the Tide” campaign is fentanyl even mentioned.

Critics of opioid prescribing have long maintained that opioid pain medication is often a gateway drug to heroin and other illicit substances, but recent research indicates that is not true.

"Although the majority of current heroin users report having used prescription opioids non-medically before they initiated heroin use, heroin use among people who use prescription opioids for non-medical reasons is rare, and the transition to heroin use appears to occur at a low rate," researchers reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Another recent study of military veterans found there was no significant link between heroin use and legally prescribed opioids or chronic pain.

Further compounding the problem is that some heroin and fentanyl deaths are falsely reported as overdoses from opioid pain medication due to inadequate or nonexistent toxicology tests.