The Real Reasons People Become Addicted

/By Dr. Lynn Webster, PNN Columnist

The Atlantic recently published an article, “The True Cause of the Opioid Epidemic,” that shares an underreported view of the complexities of the opioid crisis. The article acknowledges the epidemic is a multi-faceted drug problem that is largely driven by economic despair.

Yet most of the media remains focused on the large volume of opioids being prescribed, while ignoring the fact that opioids fill a demand created by deeply rooted, unaddressed societal problems.

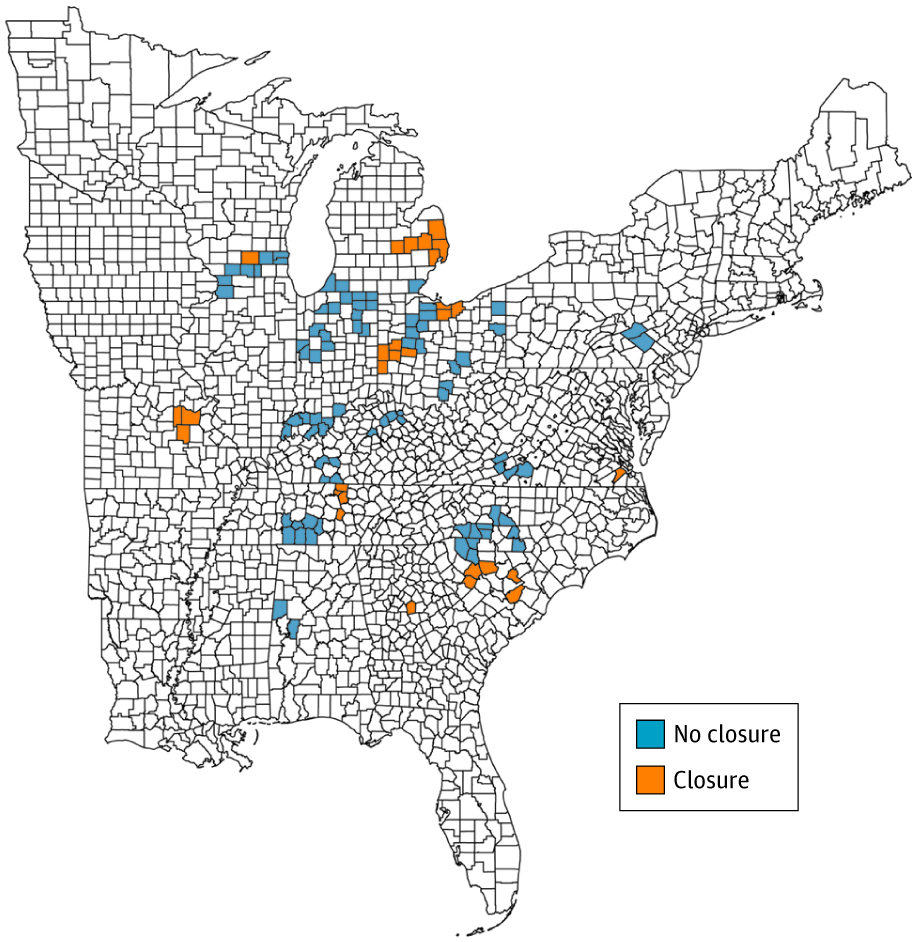

As PNN reported, a recent study found that auto plant closures in the Midwest and Southeast created a depressed economic environment where drug abuse thrived. Poverty and hopelessness, more than overprescribing, were the seeds of the opioid crisis.

But those factors are only part of the issue. The prevalence of mental health disorders, the lack of immediate access to affordable treatment of addiction, and inadequately treated chronic pain — along with poverty and despair — have caused and sustained the continuing drug crisis.

One of the challenges in beginning to solve the crisis is to change how we view people with the disease of addiction. Rather than provide them with access to affordable healthcare, we stigmatize and criminalize them. This creates recidivism rather than rehabilitation. It affects people who use drugs for the wrong reasons, as well as people who use opioids for severe chronic pain.

Debunking Myths About Addiction

Many people make another false assumption. They claim that opioid addiction develops solely because of exposure to the drugs. That is untrue. Genetic and environmental factors determine who will become addicted. Exposure to an opioid — or any drug of abuse — is necessary for the expression of the disease, but by itself it is insufficient to cause it.

Most Americans are exposed to opioid medication at some point in their lives. In fact, the average person experiences a total of nine surgical and non-surgical procedures in a lifetime. An opioid analgesic is administered during most of these procedures and is often prescribed afterward for pain control. The lifetime risk for developing an opioid addiction is less than one percent of the population.

If exposure alone were responsible for addiction, then the 50 million Americans who undergo an operation every year, or those who undergo nine procedures in a lifetime, would develop an addiction.

Commonly, people who investigate and discuss opioid overdoses believe the deaths are exclusively due to the disease of addiction. But here again, they are mistaken.

An estimated 30 percent or more of overdoses are believed to be suicides. Why do some people choose to intentionally overdose? One driver is the despair that develops from inadequately treated pain. People in pain are almost three times as likely as the general population to commit suicide. They often use drugs rather than violent acts to end their lives.

In addition, efforts to curb opioid prescribing have pushed many people to the streets to purchase illegal and more lethal drugs. This is even true for people without a substance abuse disorder who are seeking pain relief.

Despite a more than 30 percent decline in opioid prescriptions over the past decade, there has been a continued surge in drug overdose deaths. We are seeing a shift in the reasons why people are dying from overdoses. Since 2018, the number of overdose deaths from methamphetamines has exceeded the number of deaths from prescription opioids. This underscores the fact that the problem is less about the supply of opioids and more about the demand for relief of psychological or physical pain.

Clearly, America’s drug crisis involves more than just the overprescribing of opioids — and this helps explain why interventions to reduce prescriptions have not succeeded. Understanding the actual causes of the problem may help us find real solutions. It also would change the focus from people in pain who find more benefit than harm in opioids to those who clearly are at risk of harm from them.

Lynn R. Webster, MD, is a vice president of scientific affairs for PRA Health Sciences and consults with the pharmaceutical industry. He is author of the award-winning book, “The Painful Truth,” and co-producer of the documentary, “It Hurts Until You Die.” You can find Lynn on Twitter: @LynnRWebsterMD.

Opinions expressed here are those of the author alone and do not reflect the views or policy of PRA Health Sciences.