Drug Overdose Rates Rise in Rural Areas

/By Pat Anson, Editor

Rates of drug overdose deaths in rural areas of the United States now exceed those in urban areas, according to a new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CDC researchers say the overdose rate in non-metropolitan (rural) areas was 17 deaths per 100,000 people in 2015, which was slightly higher than urban areas (16.2 deaths). Both rates are substantially higher than they were a generation ago. About 52,000 Americans died of drug overdoses in 2015.

“The drug overdose death rate in rural areas is higher than in urban areas,” said CDC Director Brenda Fitzgerald, MD. “We need to understand why this is happening so that our work with states and communities can help stop illicit drug use and overdose deaths in America.”

In 2015, both urban and rural areas experienced significant increases in the percentage of people aged 26 and older who reported illicit drug use in the past month.

One of the few bright spots in the CDC report is that use of illicit drugs by adolescents (aged 12-17 years) has declined for the last ten years.

The report did not go into detail on what drugs were being abused, although it acknowledges the declining role of prescription opioids in the overdose crisis.

“Although prescription drugs were primarily responsible for the rapid expansion of this large and growing public health crisis, illicit drugs (heroin, illicit fentanyl, cocaine, and methamphetamines) now are contributing substantially to the problem,” the report found.

“Recent studies suggest that a leveling off and decline has occurred in opioid prescribing rates since 2012 and in high-dose prescribing rates since 2009.”

Curiously, while those studies have documented the increased role of heroin, illicit fentanyl and other illegal opioids in the overdose crisis, the federal government’s public awareness campaigns remain focused on prescription opioids.

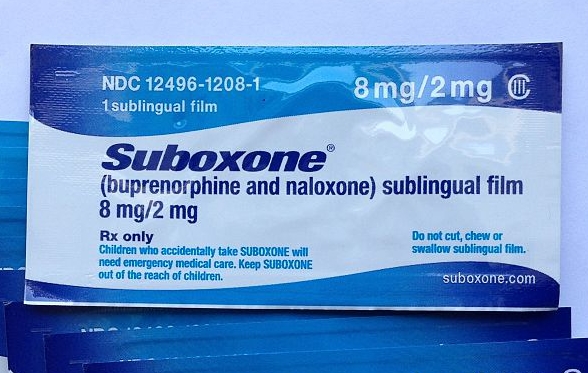

Heroin and fentanyl are barely even mentioned in the Department of Health and Human Services’ “5-Point Strategy to Combat the Opioid Crisis.” The strategy focuses instead on “advancing better practices for pain management,” and increasing access to addiction treatment and overdose prevention drugs.

The CDC also recently launched an advertising campaign using billboards and videos that completely ignore the scourge of heroin and fentanyl. The CDC explained the omission by saying it wanted to focus on prescription opioids and avoid “diluting the campaign messaging.”

“Prescription opioids can be addictive and dangerous,” a woman says in one CDC ad.

“One prescription can be all it takes to lose everything,” a man says in another ad.

Five public health experts interviewed by Pacific Standard questioned whether the CDC campaign will be effective, because the ads don't empower people or give them an alternative to prescription opioids.

"The campaign isn't going to make a damn bit of difference," said Bill DeJong, a professor of community health sciences at Boston University.