Opioid Prescriptions Plunge to 15-Year Low

/By Pat Anson, Editor

The volume of opioid prescriptions in the United States has fallen sharply and now stand at their lowest levels since 2003, according to data released by the Food and Drug Administration.

Over 74 million metric tons of opioid analgesics were dispensed in the first six months of 2018, down more than 16 percent from the first half of 2017. Opioid prescriptions have been declining for several years, but the trend appears to be accelerating as many doctors lower doses, write fewer prescriptions or simply discharge pain patients.

“These trends seem to suggest that the policy efforts that we’ve taken are working as providers, payers and patients are collectively reducing some of their use of prescription opioid analgesic drugs,” said FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, in a statement.

SOURCE: FDA AND IQVIA

"This graph confirms the perception that many of use have, that prescribing continues to decline," said Bob Twillman, PhD, Executive Director of Academy of Integrative Pain Management. "But, the question remains --what is the effect of this decreased prescribing on people with chronic pain?

"Measures of prescribing need to be matched with measures of patient function and quality of life, especially given evidence that decreased prescribing may actually be associated with increased suicide. All this measure really tells us is that the intense pressure from legislators, regulators, and payers has had its desired effect of driving down prescribing, even it there’s no evidence that it’s done anything else helpful."

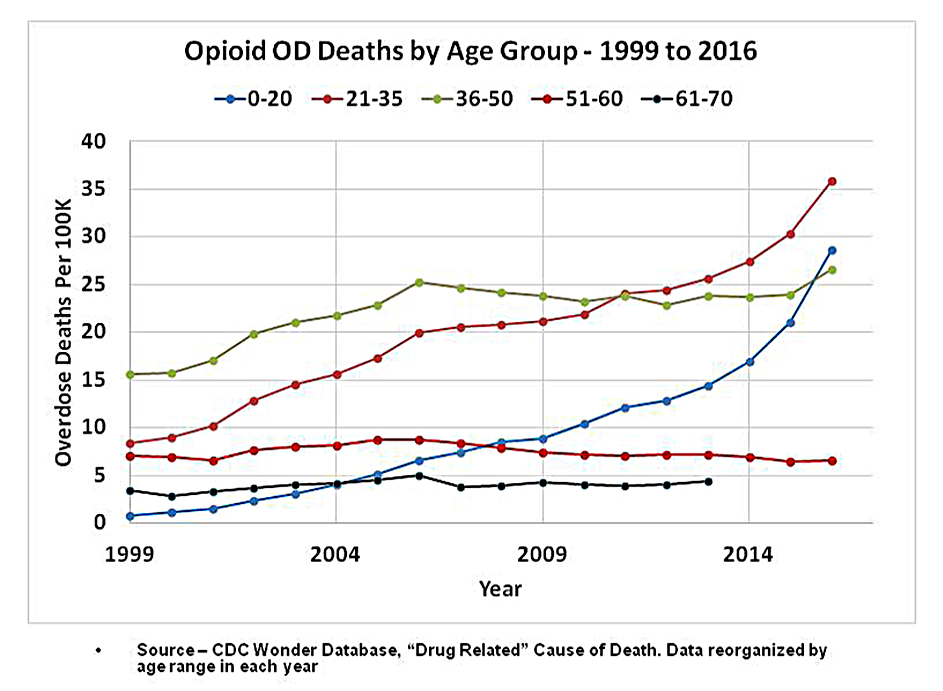

While opioid prescriptions decline, overdoses continue to rise. According to preliminary data from the CDC, nearly 49,000 Americans died from opioid overdoses in 2017, over half of them due to illicit fentanyl and heroin, not prescription opioids.

“It isn’t necessarily the case that more people are suddenly switching from prescription opioids to these illicit drugs. The idea of people switching to illicit drugs isn’t new as an addiction expands, and some people have a harder time maintaining a supply of prescription drugs from doctors,” said Gottlieb. “What’s new is that more people are now switching to highly potent drugs that are far deadlier. That’s driven largely by the growing availability of the illicit fentanyls.”

Illicit fentanyl and its chemical cousins are synthetic opioids, 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine. They are produced largely by clandestine drug labs in China and then smuggled into the U.S., where they are often mixed with heroin, cocaine and counterfeit drugs. A record 1,640 pounds of fentanyl and nearly 5,500 pounds of heroin have been seized by law enforcement so far this year; likely a small fraction of what’s available on the black market.

While the Trump administration has expanded efforts to stop the distribution and sale of illicit opioids, it also remains focused on reducing the supply of prescription opioids. The FDA plans to develop new prescribing guidelines for treating short-term, acute pain that will likely set a cap on the number of pills that can be prescribed for certain medical conditions.

“No more 30-day prescriptions for a tooth extraction or an appendectomy,” said Gottlieb.

The Justice Department also recently announced plans to lower production quotas by 10% next year for six widely prescribed opioid medications. The goal of the administration is to reduce opioid prescriptions by a third in the next three years.

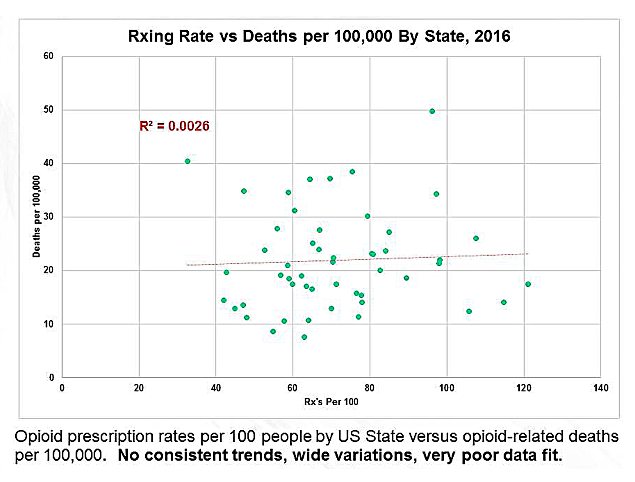

“The number of opioid prescriptions is only one of many factors and may not be the most important factor contributing to the opioid crisis. In fact, the U.S. is at a 15-year low in the amount of opioid prescribed but continues to see a surge of drug overdoses,” said Lynn Webster, MD, a pain management expert and past president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

“Much of the effort to curb the amount of prescription opioids has contributed to more suffering by people in chronic pain and possibly the increase in suicides. It also hasn't done anything to curb the number of overdose deaths. Rather than being focused on number of pills or amount of opioid prescribed we need to focus on what is the best and most appropriate treatment for individual patients. When that is done properly, the right amount of opioids will be prescribed.”