Is the DEA Overreaching Its Authority?

/By Lynn Webster, MD, PNN Columnist

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) does not have the legal authority to determine which health care activities constitute a “legitimate medical purpose.” However, an increasing number of prescribers have been subjected to DOJ criminal investigations that operate under an expanded interpretation of federal law.

In 1970, Congress passed and President Nixon signed into law the Controlled Substances Act (CSA). In its broadest sense, the CSA regulates every aspect of controlled substances, from production to delivery, distribution, prescribing, possession and use. The CSA’s impact is far-reaching, touching many different sectors of our society, including healthcare, pharmaceuticals, law enforcement, politics, and state and federal judiciaries.

According to the CSA, a prescription for a controlled substance “must be issued for a legitimate medical purpose by an individual practitioner acting in the usual course of his professional practice.” This statutory language is at the root of the issue. But who decides what is a legitimate medical purpose?

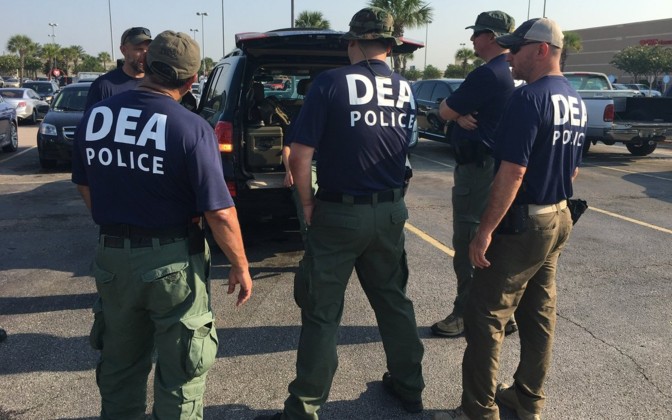

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) is the branch of the DOJ that is tasked with enforcing the controlled substances laws and regulations of the United States.

In the context of trying to address the opioid crisis, the DEA has taken a proactive approach in determining which medical practices have a legitimate medical purpose and which do not. This hands-on approach is in direct contravention with the CSA.

The DEA is effectively preempting state law as it relates to the regulation of controlled substances. In Gonzales v. Oregon, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2006 that the authority to determine a legitimate medical purpose rests with state governments.

This means it is state lawmakers, not federal officials, who should regulate the practice of medicine. Medical boards are established by the authority of each state to protect the health, safety and welfare of patients through proper licensing and regulation of physicians and other practitioners.

If a doctor engages in an obviously nefarious activity, such as selling or trading prescriptions for sex or money, then that doctor is not in any way prescribing for a legitimate or legal medical purpose under the CSA. Remedies for this conduct would be within the authority of the DOJ, as well as state regulators.

The key phrases -- "legitimate medical purpose" and "in the usual course of a professional practice" -- are not defined in the CSA. This omission, unfortunately, has invited conjecture about the meaning of the phrases in recent years. The only way the phrase "legitimate medical purpose" would have any legal meaning would be if the concept of an "illegitimate medical purpose" were defined by the CSA -- and it is not.

Moreover, the words "legitimate" and "medical" are redundant. The practice of medicine is inherently legitimate, according to the CSA. The phrase "legitimate medical purpose" can be reduced to "medical purpose" without changing its meaning.

Any practice that is medical is legitimate and should be deemed consistent with the CSA regulation. The CSA, in other words, precludes the possibility that doctors who prescribe high doses of opioids have behaved criminally based only on the level of doses they prescribe.

Standard of Care

The DOJ is now using deviation from the “standard of care” to determine whether or not practitioners have a legitimate medical purpose to prescribe opioids. A standard of care is generally considered the customary or usual practice of the average physician.

In an attempt to address the opioid problem, the DOJ has hired medical experts who claim that any deviation from standard of care amounts to practicing without a legitimate medical purpose. In some instances, the government's experts have even used the CDC opioid guideline’s dose recommendation as a test of whether or not the prescribing of opioids has a legitimate medical purpose.

Using deviations from "standard of care" as criteria for compliance with the CSA is in direct conflict with the Supreme Court ruling in Gonzalez v Oregon, which found that the Attorney General “is not authorized to make a rule declaring illegitimate a medical standard for care and treatment of patients that is specifically authorized under state law.”

Even substandard treatment by providers is not necessarily criminal behavior and should rarely involve prosecution by the DOJ. This is supported by a 1983 statement in a DEA newsletter that declares acts of prescribing or dispensing controlled substances lawful when they are done within the course of a provider’s professional practice. Even if a physician's behavior reflects the grossest form of medical misconduct or negligence, it is nevertheless legal.

The information provided in the newsletter isn't an opinion. It's the law.

Unquestionably, prescribers should be held to a high standard of care at all times. However, it is the responsibility of state medical boards to hold them to that standard. It is not the DOJ's role to determine the quality or boundaries of the practice of medicine.

Lynn R. Webster, MD, is a vice president of scientific affairs for PRA Health Sciences and consults with the pharmaceutical industry. He is a former president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine and the author of “The Painful Truth.”

You can find Lynn on Twitter: @LynnRWebsterMD.

The information in this column should not be considered as professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It is for informational purposes only and represents the author’s opinions alone. It does not inherently express or reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Pain News Network.