Fighting to Survive Suicidal Thoughts

/By Crystal Lindell, Columnist

(Author's note: A year ago today, on May 17, 2016, I almost killed myself. It was such a traumatic experience that I have marked the 17th of each month since then, and last night, I counted down the minutes until midnight as though I was counting down until my birthday. I had finally made it a year.

I wrote the following while I was in the darkest part of it — just days after everything happened. I never shared it publically, because I was worried about how it would be received, and I did not feel comfortable telling people about something I felt like I was still working so hard to overcome.

But take heart. I am still alive. And I have gotten lots of medical help since then, and lots of love from my family and friends. There are good days and bad days and very bad days, but they are my days because I am still here.

I hope my words will help you know that it is possible to fight the good fight against depression and anxiety, and that doing so does not mean you are weak — it means you a strong. For anyone currently battling mental health issues, you have all my love. Don’t kill yourself. We need you.)

How do you get over a broken heart?

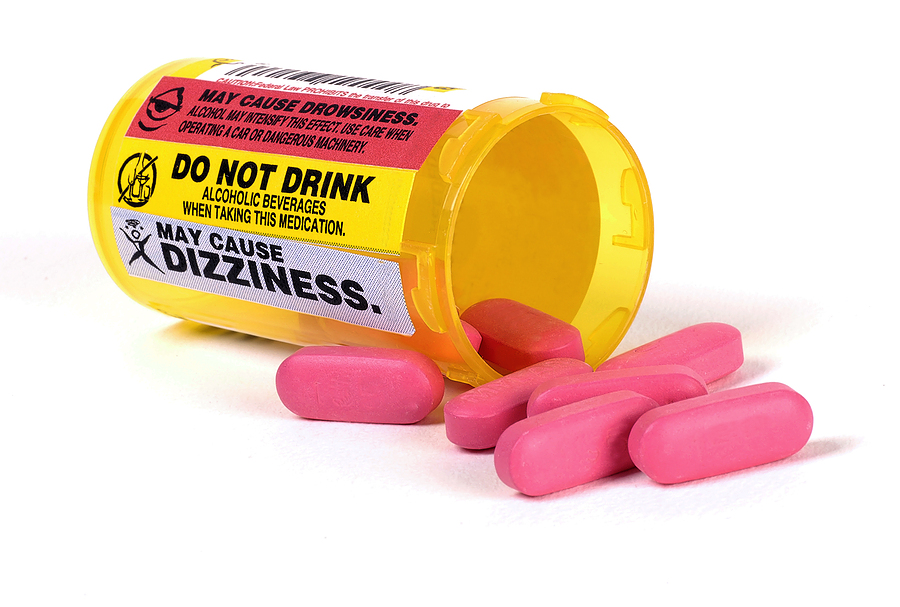

More importantly, how do you get over a broken heart when you’re having a bad reaction to your new anti-anxiety medication, BuSpar (buspirone), and it’s causing the cruelest of all side effects — increased anxiety and suicidal ideation?

How are you supposed to endure that when you’re barely standing upright in the bathroom stall at work, as your swollen eyes cry for an hour straight, and then another hour after that?

When your suddenly weak wrists are bracing your hands against the blue walls in the stall, because if they weren’t, then your legs wouldn’t be able to hold you up?

I’m actually asking. I really want to know. How do you get over that?

If you’re wondering what medication-induced suicidal ideation feels like, I will tell you. It feels like you’re planning how to kill yourself, and your brain is spinning, and you hear this voice in your head screaming, JUST DO IT. LITERALLY NOBODY WILL EVEN CARE.

It feels like the blue dress you’re wearing is suffocating you, and you just want to take all the medication in your purse, and lock the stall and die.

It feels like the pain of being alive is actually worse than death. It feels like the pain will never cease. And it feels like the only real choice you have is to kill yourself.

It feels like the hours are seconds, and at the same time, every second is an eternity.

But still, deep inside, in your soul, you hear a whisper. A piece of your heart you forgot existed, trying as hard as it can to remind you of the light. You hear the faint, barely audible voice of a little piece of yourself trying to fight it. Trying, with all its strength to remind you that maybe, just maybe there’s a couple reasons you shouldn’t kill yourself.

It’s the voice that you spent your whole life nurturing in case of emergency. Specifically, this emergency. The voice you spent years building up so that when the world is exploding it can remind you where the fire extinguisher is. And you never really think you’ll need that voice. You never really think that your life will depend on that voice.

But suddenly, there you are, suffocating in a blue dress and expensive mascara is dripping down your face, and you’re doing the math on how many meds you have in your purse, and whether or not it will be enough to kill you. And out of the blue, you need that little voice to survive.

Maybe it’s God. Maybe it’s the years of love from everyone I’ve ever known. Maybe it’s the universe. Maybe it’s all three.

It took me three days of waging war on screaming suicidal thoughts before I realized that all of this was likely a severe reaction to BuSpar, my anti-anxiety medication. I should have called my psychologist right away. And I should have gone to the ER.

But the suicidal thoughts were too loud, too overwhelming, and all the little voice in my soul could manage was continually convincing me to give it a couple minutes before I did anything too drastic. And then the minutes turned to hours, and the hours to days, and here I am, still alive.

I’m off the medication. My heart is still broken. And I’m not sure I can bear the weight of that blue dress ever again.

But I’m alive. Today, I am alive.

Crystal Lindell is a journalist who lives in Illinois. She loves Taco Bell, watching "Burn Notice" episodes on Netflix and Snicker's Bites. She has had intercostal neuralgia since 2013.

Crystal writes about it on her blog, “The Only Certainty is Bad Grammar.”

The information in this column should not be considered as professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It is for informational purposes only and represent the author’s opinions alone. It does not inherently express or reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Pain News Network.