Are Most Retired NFL Players Really Addicts?

/By Lynn Webster, MD, PNN Columnist

Many of us watched the Super Bowl on Sunday. It was a great defensive game, which means there was a lot of hard-hitting contact. Physical trauma can bring about long-term consequences and that is the subject of a recent New York Times column, "For NFL Retirees, Opioids Bring More Pain" by Ken Belson.

Belson suggests that many retired NFL players become addicted to opioid medication. I don’t know how many former players become addicted, but the summation of players he describes as addicted doesn’t quite add up.

The column cites a recent study published in the Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine that found about 26 percent of retired football players used opioid medication during the past 30 days. Belson suggests that percentage is excessive.

Of course, the players were not addicted just because they used an opioid. Moreover, 26 percent does not seem to be an unreasonable number, given that this is a population with a history of tremendous physical trauma. In fact, it seems like a surprisingly low number given that most former football players experienced enormous physical trauma for years.

Whatever the actual data may be, we can probably attribute the use or misuse of opioids to the fact that these retired players were trying to mitigate severe pain.

What is Misuse?

The accepted definition of opioid "misuse" is taking an opioid contrary to how it was prescribed, even if it is taken to treat pain. For example, let's say a person is told they can use one hydrocodone three times a day. If that person uses one pill six times a day so they can function (and not to get high), that is considered misusing. However, that is not a sign of addiction. It only reflects the person's desire to escape pain and the therapeutic inadequacy of the prescribed medication.

Misuse of opioids in the general population is relatively rare, according to a large new study published in the journal Pharmacoepidemiology & Drug Safety. Over 31,000 adults were surveyed about their opioid use, and only 4.4% admitted taking a larger dose or a dose more frequently than prescribed.

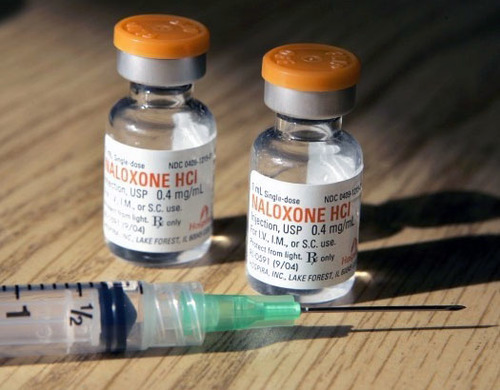

The figure below helps explain the relationships of misuse, abuse and addiction. Some retired football players may misuse their medication, but few will abuse them and even fewer will become addicted. All people with addiction abuse their medication. But people who misuse their medication may not be abusing or addicted to it.

In his column, Belson cites a 2011 survey by researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine that found over half of former NFL players used opioids during their playing careers and 71 percent misused them.

The same study found that many of these retired players who misused opioids were heavy drinkers. But in his column, Belson reported that "players who abused opioids” were likely to be heavy drinkers.

Belson uses the words “misuse” and “abuse” interchangeably, as if they have the same meaning. They do not. If Belson means that retired players took opioids in excess of what their doctors prescribed due to uncontrolled pain, that would not be abuse. It would be misuse. If the players were using opioids to get high, that would be abuse.

Belson mentions one retired player using the same amount of pain medicine as a stage 4 cancer patient and suggests that is an excessive amount. However, the player's need for that amount of opioids should not surprise us. Cancer pain is not more painful than non-cancer pain. People with painful diseases and physical injuries may have pain just as debilitating as a patient dying from cancer.

It is unfortunate, but not shocking, that a retired football player would have as much pain as someone dying of cancer. When someone who does not have cancer uses excessive medication to relieve pain, we are more likely to label that as "abuse." We show more compassion to patients with cancer pain than we do toward anyone else who requires treatment for chronic pain.

Why We Need Clarity About Our Terms

Belson writes, "Now, a growing number (of players) are saying the easy access to pills turned them into addicts." That is another statement that gravely concerns me. It is misleading and consistent with the common misunderstanding of what causes addiction or even what addiction is.

Becoming dependent on opioids, becoming tolerant to opioids, requiring more opioids over time to achieve the same level of pain relief, and experiencing withdrawal if the opioids are suddenly stopped are not necessarily signs of addiction, any more than they would be if the same consequences resulted from taking a blood pressure medication or a sleep aid.

People frequently write and talk about misuse, abuse and addiction, but many of them don't know what the terms mean. This has troubling implications for the pain and addiction communities. Mislabeling and misdiagnosing people with addiction leads to harmful policies that adversely affect treatment. It even has legal implications that prevent people in pain or with addiction from accessing appropriate clinical care.

Severe chronic pain and addiction can devastate lives. But we need to know the differences between misuse of, abuse of, and addiction to medications for the appropriate policies to be implemented.

Lynn R. Webster, MD, is a vice president of scientific affairs for PRA Health Sciences and consults with the pharmaceutical industry. He is a former president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine and the author of “The Painful Truth: What Chronic Pain Is Really Like and Why It Matters to Each of Us.”

You can find Lynn on Twitter: @LynnRWebsterMD.

The information in this column should not be considered as professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It is for informational purposes only and represents the author’s opinions alone. It does not inherently express or reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Pain News Network.