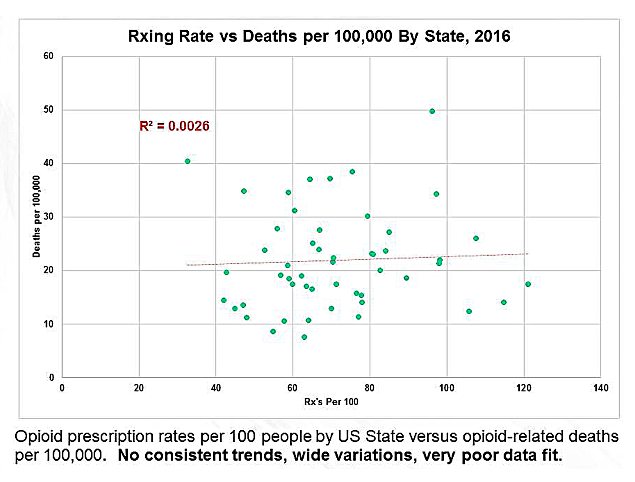

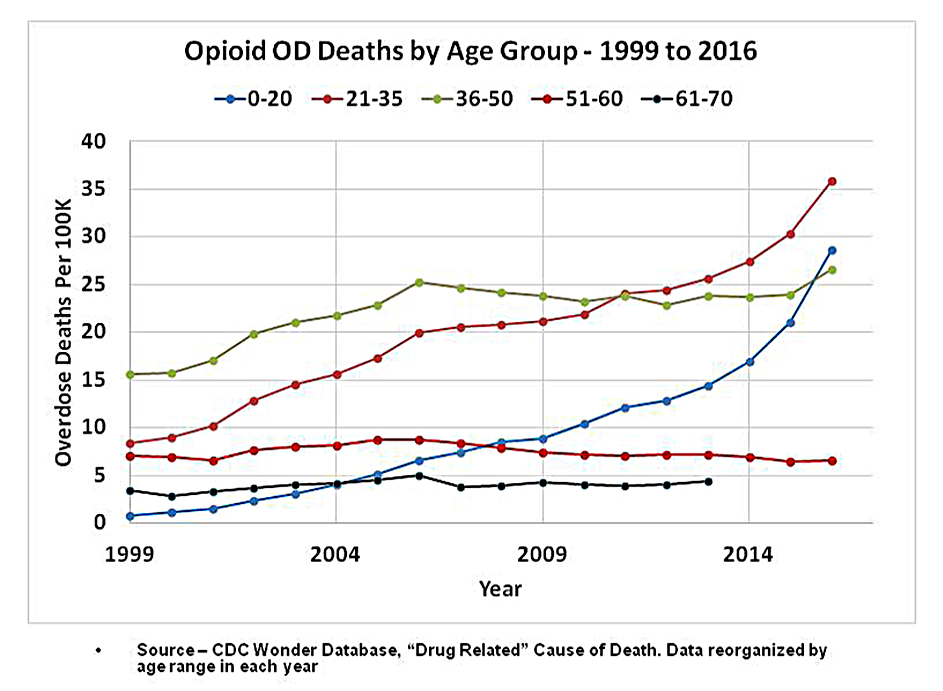

We know that rates of opioid prescribing for seniors are at least 250% higher than for kids under 21. Thus, the group that benefited the most from liberalized prescribing policies of a decade ago – older adults -- has shown no higher risk of overdose deaths, even as kids who receive fewer opioid prescriptions are now dying in record numbers.

The asserted demographics of “over-prescribing” are plainly wrong. They don’t work and never have. Exposure to medically managed opioids does not cause increased opioid mortality, at least not directly.

Brief exposure to prescription opioids contributes very little to addiction or long term use. In two recent large-scale studies, opioid abuse and prolonged prescribing of opioids were evaluated for over 650,000 patients given opioids for the first time to control pain after surgery. Fewer than 0.6% of these patients were diagnosed with opioid abuse 2.5 years later.

This means that opioid treatment for acute pain is safe, effective and usually free of bad outcomes for over 99% of opioid-naive post-surgical patients.

Do Opioid Medications Relieve Chronic Pain?

Of course they do!

We hear a lot of noise that there is no evidence or proof that opioids work for long periods. But “no proof” is not the same as “proof of no effect”.

There are very few double blind clinical trials for opioids longer than 90 days -- and this reality is entirely understandable. When people with severe pain are given placebos, they lapse into agony and drop out of trials. Long term studies of any pain treatment can easily rise to the level of being inhumane – which is why so few have been conducted.

It isn’t rocket science, and the writers of the CDC guideline knew it. Instead of comparing shorter trials of opioid analgesics against behavioral therapies and non-opioid medications, the guideline writers stacked the deck against opioids. And they got caught at it by their medical peers.

If trials of all three therapies had been limited to studies of at least a year -- as opioids were but alternative therapies were not -- none of the three could have provided “evidence” of useful effect.

We must also acknowledge that not all patients do well on opioids. Some develop persistent nausea, sedation, constipation, suppression of sexual libido and depression. Some patients also become drug tolerant, requiring ever-increasing doses of opioids to achieve the same pain-relieving effects. It has been theorized that a condition called “opioid induced hyperalgesia” may alter the action of opioid receptors in the brain. But there is no medical consensus on how to measure such an effect in human beings, or even whether hyperalgesia exists.

Many of the perceived failures of opioid therapy might be laid at the feet of ill-trained physicians. Some doctors titrate their patients from zero to a therapeutic dose too fast. Others fail to recognize factors in liver metabolism which make some patients poor metabolizers or hyper-metabolizers of opioids. Variation in metabolism means that there can be no one-size-fits-all pain treatment. Opioid therapy can be safe and effective for a small minority of patients at doses well above 1,000 MME.

Are Safe Substitutes for Opioids Widely Available?

For millions of patients, not yet.

We hear a lot of noise about tapering pain patients out of opioid therapy and into “alternative” or “integrative medicine.” Indeed, it seems appropriate to first try less powerful medications such as NSAIDs or anticonvulsants before proceeding to opioids. Exercise and massage therapy are also useful as palliative therapies. But for millions of people, less powerful medications don’t work well enough -- or at all. Tylenol or ibuprofen at high doses might also put you in a hospital with liver toxicity or major gastrointestinal problems.

What about “non-pharmacological” and “non-invasive” therapies? Do they work well enough to be substituted for opioids? Unfortunately, the answer is no. The state of science for alternatives like cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture, chiropractic, or various talk therapies is simply abysmal.

At most, these alternative treatments are experimental. They might be useful as supportive therapies in coordination with a well managed program of pain relieving medications. But pending a more rigorous evaluation, we simply cannot offer such experimental techniques as substitutes for opioids.

What Are Federal Agencies Doing to Correct Course?

In two words, “nothing apparent.”

The CDC, Food and Drug Administration, Health and Human Services (HHS), and the National Institutes of Health seem to be collectively dragging their feet in a campaign of deliberate inaction, refusing to respond to criticism or examine their own medical evidence of error.

This author and others have been trying for years to get healthcare agencies to reevaluate the relationship between opioid prescribing and overdose mortality. These efforts have included recent testimony to the FDA Opioid Policy Steering Committee and to the HHS Inter Agency Task Force on Best Practice in Pain Management.

In addition, copies of our analysis have been sent to the following authorities. Most have been silent and none have responded in substance.

- Dr. Scott Gottlieb, FDA Commissioner and senior analytics staff

- Dr. Sharon Hertz, Director, Division of Anesthesia, Analgesia, and Addiction Products, FDA

- Dr. Mary Kremzner, Director, Division of Drug Information, FDA. (Dr. Kremzner responded with a courteous letter referring to a press release from Scott Gottlieb).

- Alicia Richmond Scott, Designated Federal Officer, and Dr. Vanilla Singh, Chair of the HHS Inter Agency Task Force on Best Practices in Pain Management

- Dr. Nora Volkow, Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse

- The Whistleblower gateway of the House Subcommittee on Government Oversight

An inquiry was also filed online with the CDC. A dismissive response was received from the CDC Center for Injury Prevention – which oversaw development of the opioid guideline -- claiming to have read my analysis and asserting their previous positions. This response was clearly a brush-off adapted from previous form letters.

A request is now in preparation to the HHS Office of the Inspector General, asking for investigation of CDC for malfeasance and possible fraud.