Pain Warriors: A Civil Rights Movement for Our Time

/By Pat Anson, PNN Editor

A long-awaited documentary about chronic pain in North America is shining a light on the other side of the opioid crisis – how chronic pain patients and their doctors have been marginalized and persecuted in the name of fighting opioid addiction.

“Pain Warriors” is being released by Gravitas Ventures. It is available for streaming on Vimeo, iTunes and Amazon Prime or on DVD.

The 80-minute film takes an intimate look at the lives of four chronic pain patients and their loved ones, including an 11-year old boy living with cancer pain and a doctor who nearly lost his medical license due to allegations he overprescribed opioids.

Two of the “pain warriors” featured in the documentary commit suicide after losing all hope that their pain will be properly treated.

“That captures the essence of our film -- invisible, shunned and disbelieved. This is the story of their fight. Pain Warriors is a civil rights movement for our time,” says Tina Petrova, who produced and directed the documentary along with filmmaker Eugene Weis.

“Doctors have been incarcerated, committed suicide, gone broke standing up for appropriate treatments for intractable pain. Families have lost loved ones due to suicides from chronic pain and medical complications such as spinal leaks. This is no small disease. It steals husbands and wives, sons and daughters.”

Pain Warriors is dedicated to Sherri Little, a California woman who took her life at the age of 53 after a last desperate attempt to get treatment for her fibromyalgia and colitis pain. (See “Sherri’s Story: A Final Plea for Help”). Sherri was a good friend of Petrova, who is well-acquainted with the issues faced by chronic pain patients – because she’s one herself.

“I began pre-interviews for the film around 2014, gathering collections of heartbreaking, compelling stories. A pain patient struggling with her own pain demons donated money to the cause, wanting her story told alongside others, and we began making the film in earnest,” she told PNN.

“Has it been easy? I’d say it’s been a hell of a lot of painstaking work by all involved, including the cast, who bravely offered up their vulnerability and very intimate stories. Has it been worth it? Absolutely.”

You can see a preview of Pain Warriors here:

The release of Pain Warriors was initially delayed due to funding problems, and then because Petrova suffered a severe back injury during physical therapy. She was bedridden and housebound for over a year.

“I’m hopeful that I’m on the mend at long last, and will be able to take the film across North America, once COVID restrictions are lifted, and lead in-person screenings with the people the film was made for -- chronic pain patients and the healthcare professionals that sometimes risk everything fighting for their rights,” says Petrova.

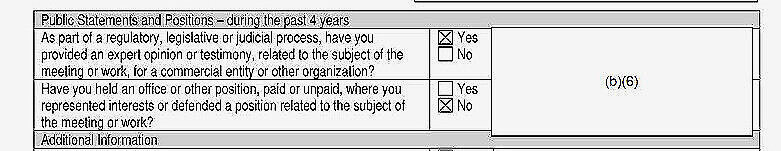

Dr. Mark Ibsen plays a prominent role in the film. The Montana Board of Medicine suspended Ibsen’s medical license in 2016, a decision that was reversed two years later when a judge ruled the board made numerous procedural errors.

Ibsen’s legal battles have not ended. The Board of Medicine has refused to formally close his case, leaving Ibsen in professional limbo. Pharmacists won’t fill his opioid prescriptions and he was forced to close his urgent care clinic in Helena. Now he travels the back roads of Montana writing prescriptions for medical marijuana.

“I’ve been marginalized,” says Ibsen, who plans to sue the Board of Medicine for monetary damages. “Anything the board would say would not completely clear me. I need the judge to say, ‘This is bogus. Stop it. Dismiss the case.’”

Pain Warriors is featured in PNN’s Suggested Reading section, where you can buy the DVD through Amazon.