A Careful Reading of 'Dopesick'

/By Roger Chriss, PNN Columnist

The new book “Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company That Addicted America” by Beth Macy describes the origins of the opioid crisis and the plight of people addicted to opioids, particularly in the Roanoke area of Virginia.

The book looks at the crisis from multiple perspectives, including local physicians and pharmacists, law enforcement and attorneys, community leaders and even drug dealers. Macy treats the story of opioids, addiction, and fatal overdose with sympathy and concern.

“Until we understand how we reached this place, America will remain a country where getting addicted is far easier than securing treatment,” she wrote.

Macy relies heavily on books like “Painkiller” by Barry Meier and “American Pain” by John Temple, asking questions these journalists explored but providing no new answers. In so doing, she perpetuates numerous media-driven myths about the crisis and misses opportunities to investigate important open questions.

Dopesick starts with the arrival of Purdue Pharma’s OxyContin and the rapid rise of addiction and overdose. Appalachia was among the first places where OxyContin gained a foothold in the mid-1990s, quickly ensnaring working class families:

“The town pharmacist on the other line was incredulous: ‘Man, we only got it a month or two ago. And you’re telling me it’s already on the street?’”

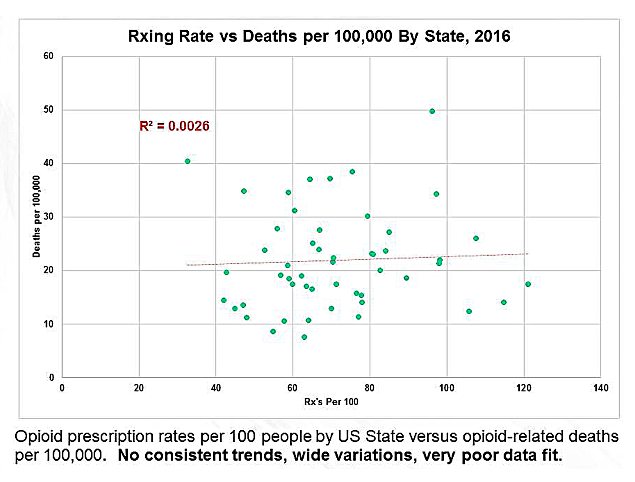

It is still not clear how OxyContin made it into the black market so deeply and quickly, but Macy concludes that overprescribing for chronic pain was a key factor in the crisis. She cites “recent studies” that the addiction rate for patients prescribed opioids was “as high as 56 percent."

Most studies actually put the addiction rate much lower, with the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) estimating it at 8 to 12 percent.

In the second part of Dopesick, Macy draws on the work of Stanford psychiatrist Dr. Anna Lembke in describing adolescent drug use:

“Across the country, OxyContin was becoming a staple of suburban teenage ‘pharm parties,’ or ‘farming,’ as the practice of passing random pills around in hats was known.”

But pharm parties were debunked years ago as an urban legend. Slate’s Jack Shafer looked into their origin and concluded the “pharm party is just a new label the drug-abuse industrial complex has adopted."

Macy’s writing often echoes her source materials. On adolescent drug use, she writes:

“So it went that young people barely flinched at the thought of taking Adderall to get them going in the morning, an opioid painkiller for a sports injury in the afternoon, and a Xanax to help them sleep at night, many of the pills doctor prescribed."

Lembke herself wrote in the book ”Drug Dealer, M.D.” in 2015:

“Many of today’s youth think nothing of taking Adderall (a stimulant) in the morning to get themselves going, Vicodin (an opioid painkiller) after lunch to treat a sport’s injury, ‘medical’ marijuana in the evening to relax, and Xanax (a benzodiazepine) at night to put themselves to sleep, all prescribed by a doctor."

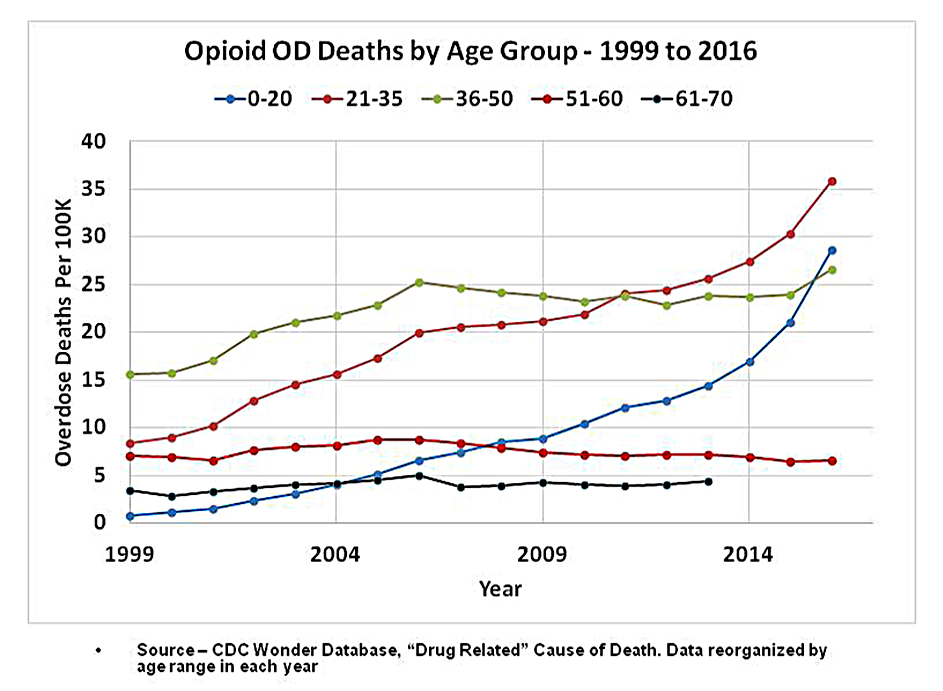

The similarities between Macy and Lembke (a board member of the anti-opioid group Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing) are striking. More importantly, the data on teenage drug use disagrees with both of them. According to NIDA, teen drug use has been in decline for most substances for the past 10 years. Which makes it hard to parse Macy’s and Lembke’s claims about high levels of medication misuse among the teenagers they describe.

Macy also perpetuates ideas about race in the crisis: “Doctors didn’t trust people of color not to abuse opioids, so they prescribed them painkillers at far lower rates than they did whites.”

“It’s a case where racial stereotypes actually seem to be having a protective effect,” she quotes PROP founder and Executive Director Andrew Kolodny, MD.

In fact, rates of addiction and overdose have been rising rapidly among African Americans for years and recent CDC data on ethnicity in overdoses shows no significant difference among black, white, and Hispanic populations. The crisis has long since evolved beyond omitting a particular minority group.

Why did it take so long to recognize the opioid crisis and work to stop it? Macy assigns blame to the political unimportance of regions like Appalachia, the failure in many states to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, and addiction treatment that’s based on 12-step or abstinence-only programs. She writes about the treatment industry with almost righteous anger:

“An annual $35 billion lie -- according to a New York Times exposé of a recovery industry it found to be unevenly regulated, rapacious, and largely abstinence-focused when multiple studies show outpatient MAT (medication assisted therapy) is the best way to prevent overdose deaths.”

“The battle lines over MAT persist in today’s treatment landscape -- from AA rooms where people on Suboxone are perceived as unclean and therefore unable to work its program, to the debate between pro-MAT public health professionals and most of Virginia’s drug-court prosecutors and judges, who staunchly prohibit its use.”

But Macy doesn’t look at the full story that heroin addiction represents. She omits the shattered childhoods and serious mental illness often seen in heroin users, and ignores the complicated trajectory of substance abuse. She also skips the fact that heroin addiction frequently starts without prior use of any opioids.

Throughout the book, Macy follows the standard media narrative of the crisis, focusing on addiction as a result of pain management gone wrong. But most people who become addicted to opioids start with alcohol, marijuana and other recreational drugs.

What Dopesick may lack in depth and rigor, it makes up for in compassion and intensity. Unfortunately, Macy accepts at face value claims from experts when she should have fact-checked them. Perhaps the errors will be corrected in a second edition, which could turn an interesting book into essential reading.

Roger Chriss lives with Ehlers Danlos syndrome and is a proud member of the Ehlers-Danlos Society. Roger is a technical consultant in Washington state, where he specializes in mathematics and research.

The information in this column should not be considered as professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. It is for informational purposes only and represents the author’s opinions alone. It does not inherently express or reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of Pain News Network.